G. Charles was a very loving and affectionate father, who took his young children with him everywhere that he went, when they were not in school. He shared a passion for law with his adoring daughter, Jane, and would answer her many questions about the intricacies of his profession. She spent hours with him in his law office after school, as well as during some weekends. Jane came to admire his extensive library of leather-bound legal books, which “intrigued her,� as she later recalled. She indeed inherited her father’s love of law- and decided for herself, early on, that she also wanted to become a lawyer.

She later said, in an interview with the Poughkeepsie Journal, “As the youngest child, and motherless from the age of 8, I was always very close to my father and I guess spoiled by him. However, it was not until I was grown and had my own family and was widowed that I truly appreciated his unselfish devotion to his children.”

Jane’s decision about the discipline of law, in which she would later engage, was shaped by her exposure to the plight of black people in America during those times. Having led a previously sheltered lifestyle, that exposure came through her father’s committed involvement in the NAACP. Jane faithfully read every edition of The Crisis, the NAACP’s bi-monthly magazine (founded in 1910 by W.E.B. Du Bois), from cover to cover. It was within those pages, which regularly published photos of lynching victims from across the country, that Jane’s sheltered life was shaken. The violent racism and hatred directed at black people was a world away from the microcosm that she grew up in, where her father was respected and admired by both black and white, and she was generally protected from the prejudice that divided the country.

She dedicated herself, and her passion for law, to helping others.

After graduation from Poughkeepsie High school in 1924, at only 15 years of age, the brilliant Jane would follow in her father’s footsteps. She enrolled in a prestigious Massachusetts undergraduate college, with the intent to major in law. She attended Wellesley College, a liberal arts college for women near Boston, and was one of only two black students there. Both immediately ostracized and ridiculed by the entire student body, they decided right away to live off campus, and become roommates. This was Jane’s first taste of blatant racism. Jane later recalled that the majority of her days at Wellesley were “sad and lonely.�

“There were a few sincere friendships developed in that beautiful, idyllic setting of the college,â€� Jane remembered, “but on the whole, I was ignored outside the classroom.“

Despite a lack of encouragement and respect from most of her professors, Jane graduated as one of the top 20 students of her class in 1928, and was officially designated a “Wellesley Scholar.�

Jane knew that the treatment she had received from faculty throughout her matriculation, would only continue during the obligatory meeting with Wellesley’s career advisor for graduating seniors. As expected, the advisor told Jane that she should not pursue a legal career, as there would be no work for a black woman as an attorney. When she made it clear that she would not only pursue a career in law, but intended to apply to Yale Law School to continue her studies, she was mocked and told that she should aim lower… as she would never be accepted at such a prestigious institution.

Even Jane’s father tried to dissuade her from applying to Yale, only seeking to shield her from further prejudice, as he had once been able to do when she was a child. He made the case that the law profession revealed the worst in human nature. He preferred that Jane instead become a teacher- where she could help instruct, encourage, and inspire black students to pursue an advanced education and make great advances for the black community. Jane felt that she would be an even greater inspiration, by doing those things herself, as a pioneer in her chosen field. Little did G. Charles know at the time that he was making his case, that Jane had already been accepted at Yale. When her father learned this, he relented, and gave Jane his full support.

Emboldened and unintimidated through her experience at Wellesley, Jane enrolled at Yale Law School that same year- as the only black woman, and only one of three women in total, matriculating there.

Three years later, in 1931, Jane became the first African American woman to receive a law degree from Yale. She easily passed the New York State Bar exam the following year, after returning home. She was now able to practice law in the state of New York. She did so, at her father’s law firm, getting her feet wet in the profession while under her father’s continued mentorship.

While practicing at her father’s firm, Jane met and fell in love with Ralph Mizelle, also an area lawyer. They married in 1933, and moved to New York City, to start a practice there together. Ralph would continue to run the practice, while Jane would eventualy set the stage for her calling in public service, four years later.

In 1937, Jane would be hired for her first public position. She was named Assistant Corporate Counsel for the City of New York. Upon being hired on the spot by the lead counsel (after some initial prejudice by an administrative assistant), Jane was the first woman ever to be hired for this position. She had previously run, unsuccessfully, for a seat in the New York State Assembly as the Republican candidate in her district the year before.

Having served in this capacity for two years, she was informed one day that the Mayor had requested to see her. The Mayor sent instruction that she was to meet him at the newly opened New York City Building at the World’s Fair in Flushing Meadows-Corona Park, Queens. For the entire commute from Manhattan to Queens, Jane worried that she would either be reprimanded or fired, though she could recall nothing that she may have done wrong.

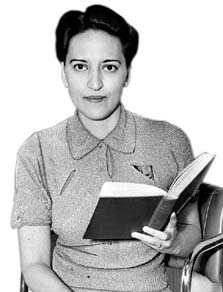

To her surprise, after two years of exemplary service to the city, Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia elevated Jane to an historic appointment. On July 22, 1939, the 31 year old Jane Bolin was sworn in by LaGuardia to be Judge of the Domestic Relations Court (later renamed to Family Court in 1962). It was then that she became the first female African American judge of any court in the U. S. She thrived in and relished this position, discovering her calling in law, and exacting some monumental changes in the legal system relative to family law and civil rights. Incidentally, Jane’s husband, Ralph was not as surprised as she was about the Mayor’s plans to swear her in. He had consulted with Ralph beforehand, about the best way to catch her off guard. He called Ralph and some photographers out of a private room, to also surprise her for the ceremony.

Some of the revolutionary changes that she is known for, include ending the practice of assigning probation officers to individuals according to race. She made it illegal for race to be a consideration in the officer assignment process.

She also mandated that private childcare agencies which received public funds must accept all children, regardless of race or ethnicity. Previously, there had been a general problem, for African American working parents to secure decent and reliable childcare. She became an activist for children’s rights, and later helped to establish a racially integrated center for troubled youth.

Judge Bolin presided over many types of family cases- ranging from domestic violence, to child neglect, to adoptions, to paternity suits… every family matter with the exception of divorce cases (which are heard in the Supreme Court).

She took a leave of absence, in 1941, for the birth of her only child. He was a son, born Yorke Bolin Mizelle. Her husband, Ralph, unfortunately died two years later. As did her father, Judge Bolin would balance a career in law- with parenthood. Modeling her father’s dedication to his children, she made Yorke her main priority, while successfully maintaining her career as a means to provide for him.

“I don’t think I short-changed anybody but myself,” she recalled later. “I didn’t get all the sleep I needed, and I didn’t get to travel as much as I would have liked, because I felt my first obligation was to my child.”

Judge Bolin also remained true to her heart for civil service and civil rights, continuing her involvement with the NAACP, and rising through its ranks. She ultimately served on the NAACP’s executive committee. Being a board member on the committee which shapes the very policies of the NAACP, Bolin soon came to see however, that the organization was heading in a different direction than that which she had previously known. She noticed certain political leanings that began to influence policy, which were at odds with the principles that she continued to live by. She was eventually removed from the executive committee, as their relationship continued to sour, though later offered the position of vice president. She declined this offer, and ultimately left the organization in 1950.

She remarried that same year, to the Rev. Walter P. Offutt Jr. They had no other children, and spent 24 years together, until Rev. Offutt died in 1974.

Judge Bolin served as Family Court Judge for 40 illustrious years, having had her appointment renewed three more times by subsequent Mayors William O’ Dwyer, Robert F. Wagner Jr., and John V. Lindsay. She had reached the year of her mandatory retirement age of 70, in 1978, and was thus mandated to resign (though reluctantly) from her appointment in January of 1979.

She had probably become more active in her retirement, than during her service as judge. She became a volunteer reading instructor in various New York City schools immediately following her retirement, and was also appointed to the Regents Review Committee of the New York State Board of Regents. Bolin served on the boards of the New Lincoln School, the Dalton School, the Child Welfare League, and the National Urban League. She also received honorary degrees from Tuskeegee Institute, Williams College, Hampton University, Western College for Women, and Morgan State University.

After a life of groundbreaking achievements, The Honorable Jane M. Bolin died on January 8, 2007. She was 98. She is survived by her son, Yorke, as well as a grandaughter and a great-grandaughter.

Commenting on her life of public service, “I’ve always done the kind of work that I like. Families and children are so important to our society, and to dedicate your life to trying to improve their lives is completely satisfying.”

It is a rare thing indeed, to live a life so satisfying and so fulfilling. She has contributed tirelessly, and profoundly to our society… breaking tremendous barriers in the process. The Honorable Jane M. Bolin transcends the designation of an African-American hero, and of a woman’s hero. She has become, an American Hero, and a model for us all to emulate- regardless of race, gender, or creed.

Source: Jane Bolin Profile – American Bar Association – http://www.abanet.org/publiced/bh_jb.html