Oscar James Dunn (1826 – November 22, 1871) was one of three African Americans who served as a Republican Lieutenant Governor of Louisiana during the era of Reconstruction. In 1868, Dunn became the first elected black lieutenant governor of a U.S. state. He ran on the ticket headed by Henry Clay Warmoth, formerly of Illinois. After Dunn died in office, then-state Senator P. B. S. Pinchback, another black Republican, became lieutenant governor and thereafter governor for a 34-day interim period.

On December 22, 1866, Dunn testified before a select committee appointed to investigate the New Orleans Riot of July 30, 1866. He told the committee that he was “born in New Orleans in 1826 and was about forty-one years old”. His parents were James and Maria Dunn. His father, James Dunn of Petersburg, Virginia, had been emancipated in 1819 by James H. Caldwell in New Orleans. James Dunn became a free man of color and later emancipated his wife, Maria, and their two children, Oscar and Jane, in 1832. James Dunn worked as a carpenter for James H. Caldwell (founder of the St. Charles Theatre and New Orleans Gas Light Company); Maria Dunn ran a boarding house for actors and actresses that came to perform at the Caldwell theatres.

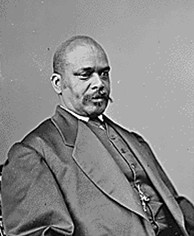

Oscar Dunn was neither a Creole of Color (gens de couleur), nor of fair complexion. He is described in an article in The New York Times on June 25, 1893 as “Jamaican, well educated, and pure African;” by September 16, 1894 the same newspaper describes Dunn as being “of pure negro blood”. Other articles have describe him as a “griffe” (32 parts white/96 parts non-white; the child of a mulatto and a pure Black). A recently published photo from the National Archive of the Mathew Brady Collection, removes all misconceptions and attempts to illustrate Dunn as anything other than what he was.

Dunn was apprenticed as a young man to the plastering and painting contractor, A. G. Wilson, who had earlier verified Dunn’s free status in the Mayor’s Register of Free People of Color 1840-1864. On November 23, 1841, Dunn was reported as a RUNAWAY by the subscribers, [A.G.] Wilson & Patterson in a newspaper ad which ran in the New Orleans Times-Picayune.

Having studied music, Dunn became both an accomplished musician and an instructor of the violin.

The social, political, and racial conditions in New Orleans were a catalyst for Dunn’s focus on equality for those blacks who had been freed througfh the Thirteenth Amendment, ratified after the American Civil War. Dunn was an English-speaking black man in a city where a self-imposed caste system was the underpinning of daily life. It was a city in which French culture was promoted as having been more refined than that established by the English speaking residents who came to the city in the early-to-mid-19th century.

Dunn was a member of Masonic lodge. In the latter 1850s, he was a Master and Grand Master of the lodge. Author James A. Walks, Jr., a Prince Hall Freemason, credits Dunn with outstanding conduct of Masonic affairs in Louisiana(the author should be Joseph A. Walkes, Jr and the name of the book he wrote is “Jno G. Lewis, Jr.–end of an era: the history of the Prince Hall Grand Lodge of Louisiana, 1842-1979” publisher J.A. Walkes, Jr., 1986; Jno G. Lewis, Jr–end of an era). Dunn refused to acknowledge any authority higher than that of the Grand Lodge for the State … and was instrumental in passing Louisiana Act No. 71 in 1869 which incorporated the Grand Lodge of Louisiana with authority to confer the first three degrees in Masonry. As a Freemason, he established a political power base useful for his political career. He resigned as Grand Master on January 9, 1868, when he was elected Lieutenant Governor of Louisiana. In 1870, however, he returned to his position as Grand Master of the Eureka Grand Lodge and held that title until his death.

During Reconstruction, Dunn opened an employment agency that assisted in finding jobs for the freedmen. He actively promoted and supported the Universal Suffrage Movement; advocated land ownership for all blacks; taxpayer-funded education of all black children; and equal protection of the laws under the Fourteenth Amendment. He was Secretary of the Advisory Committee of the Freedmen’s Savings and Trust Company of New Orleans, where he worked to insure that recently freed slave were treated fairly by former planters to who they were now contracted to perform the same duties they had once undertaken as slaves. In 1866, he organized the People’s Bakery, an enterprise owned and operated by the Louisiana Association of Workingmen.

As a New Orleans city council member in 1867, Dunn was named chairman of a committee to consider alterations to Article 5 of the City Charter. He proposed that “all children between the ages of 6-18 be eligible to attend public schools and that the Board of Aldermen shall provide for the education of all children … without distinction to color.” In the Constitutional Convention of 1867-1868, this resolution was enacted into Louisiana law and laid the foundation for the public education system.

Dunn was very active in local, state and federal politics; with connections to U.S. President Ulysses S. Grant and U.S. Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts. At a hotly contested nominating convention held in New Orleans, immediately following the adoption of the Louisiana Constitution of 1867-1868, Francis E. Dumas declined the nomination of Lieutenant Governor. Dunn was consulted and agreed to the nomination. He defeated the white candidate for the nomination, W. Jasper Blackburn, the former mayor of Minden in Webster Parish, by a vote of fifty-four to twenty-seven.

The Warmoth-Dunn Republican ticket was elected, 64,941 to 38,046 and hence launched the reign of the Radical Republican Party in state politics. He was inaugurated lieutenant governor on June 13, 1868. In that capacity, he was also the President pro tempore of the Louisiana State Senate. He was a member of the Printing Committee of the legislature and had access to a million-dollar budget. He also served as President of the Metropolitan Police with an annual budget of nearly one million dollars and responsibility for maintaining stability in a toxic political atmosphere. In 1870, Dunn served on the Board of Trustees and Examining Committee for Straight University.

In December 1866, the same month he testified before the select committee in Washington, D.C., Dunn married the widow Ellen Boyd Marchand, daughter of Mr. and Mrs Henry Boyd of Ohio. He adopted her three children, Fannie (9), Charles (7) and Emma (5). The couple had no children together. In 1870, the Dunn family residence was located on on Canal Street, one block west of South Claiborne Avenue and within walking distance of Straight University and the St. James A.M.E. church complex.

As a Radical Republican and a member of the Customshouse faction, which had differences with the Warmoth-Pinchback faction of the party, Dunn made political enemies and had questionable allies. According to The New York Times, Dunn “had difficulties with Harry Lott”, a Rapides Parish member of the Louisiana House of Representatives (1868–1870, 1870–1872). He also had problems with his eventual successor as lieutenant governor, State Senator P.B.S. Pinchback (1868–1870, Dec. 1871) over differences of policy, leadership, and direction.

On November 22, 1871, after a brief and sudden illness, while campaigning for the upcoming state and presidential elections, Dunn died at his home on Canal Street. What we know and do not know about the circumstances of his illness and death has led to many unanswered questions and given birth to many rumors. Speculation evolved regarding foul play, but the parties suspected were never identified, and Dunn’s death remains a mystery.

The Dunn funeral is said to have been one of the largest that New Orleans ever witnessed. As many as fifty thousand lined Canal Street for the procession, and newspapers across the nation recorded the event. State officials, masonic lodges, and civic and social organizations participated in the procession from the St. James A.M.E. church to his grave site. He was laid to rest in the Cassanave family mausoleum at St. Louis Cemetery No. 2.

The New Orleans Times-Picayune published a poem on the day after Dunn’s death entitled The Death Struggle:

My back is to the wall

And my face is to my foes;

I’ve lived a life of combat,

And borne what no one knows.

But in this mortal struggle

I stand—poor speck of dust,

Defiant—self-reliant,

To die—if die I must.

After his death, his widow Ellen was appointed by the mayor of New Orleans to the position of municipal archives director. On November 23, 1875, she married J. Henri Burch, a fellow member of the Customhouse faction and a former state senator from East Baton Rouge Parish. The Burch family resided in New Orleans.