The Vesey Revolt was led by Denmark Vesey (1767-1822) and to a lesser extent, by his accomplice, Peter Poyas (Higginson, 229). Vesey was a literate and very intelligent black man who had purchased his freedom in January of 1800; he was the only free black to take part in the revolt. The revolt was planned to occur on an unknown date in May of 1822 near Charleston, South Carolina (Sylvester, bio 231).

The Vesey Revolt was led by Denmark Vesey (1767-1822) and to a lesser extent, by his accomplice, Peter Poyas (Higginson, 229). Vesey was a literate and very intelligent black man who had purchased his freedom in January of 1800; he was the only free black to take part in the revolt. The revolt was planned to occur on an unknown date in May of 1822 near Charleston, South Carolina (Sylvester, bio 231).

Vesey’s views and ambitions were spurred by his work with the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church, the only independent black church in Charleston at the time. Within the church, Vesey gave sermons and led lessons. As a literate man, he was looked upon as a teacher.

His association with the AME Church gave him an outlet to express his views of equality. (Sylvester, Bio 230-232). The strong influence that religion had on Vesey, and Vesey’s biblical education are evident through the song “Go Down, Moses,” which is popularly credited to Denmark Vesey:

When Israel was in Egyptland

Let my people go

Oppressed so hard they could not stand

Let my people go

Go down, Moses,

Way down in Egyptland

Tell old Pharoah,

“Let my people go!”

The touching words of the above excerpt artfully expresses the pain felt by slaves in North Carolina before Vesey’s planned revolt (Leeming & Page, 59).

Denmark Vesey also gained inspiration from the Haitian Revolution, an event which he may himself have been a part of if his master had not been unable to sell him in St. Domingue in 1781. Only ten years later, the bloody revolution, which resulted in the creation of the black republic of Haiti, began (Sylvester, bio 230-232).

Denmark Vesey began organizing the revolt in December, 1821. He planned his attack for the summer, when the largest number of white people would be out of Charleston on vacation (Sylvester, bio 233). Denmark was careful to choose only trustworthy individuals; most of these people were artisan slaves of high intelligence (Sylvester, alma 187).

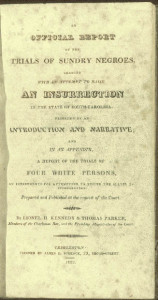

The original attack date was set for the second Sunday in July, 1822 but had to be moved forward after two conspirators were arrested on May 30. Unfortunately for the rebels, Vesey was unable to communicate the change of date to thousands of slaves, some of whom lived eighty miles away (Sylvester, alma 187-188). The attack never occurred because a house servant disclosed the plan to local authorities. Soon after, 130 blacks were arrested for their connections with the revolt (Rodriguez, 271).

Of the 130 arrested conspirators, 49 were sentenced to death and twelve were later pardoned. In the end, 36 slaves, including Peter Poyas, were hanged. Denmark Vesey was also hanged with his followers. Four white men were arrested, jailed, and fined for their roles in the revolt (Rodriguez, 271-273). The African Methodist Episcopal Church was subsequently torn down, and stricter laws were passed in many southern states to limit the movement granted and the education given to blacks in the South. Black people could no longer meet in groups for any reason without the presence of a white person; slaves could not hire out their free time; and, in South Carolina, free blacks over the age of 15 were required to have a white guardian (Sylvester, bio 234-235).