Military

Margaret E. Bailey (December 25, 1915 – August 28, 2014) was a United States Army Nurse Corps colonel. She served in the Corps for 27 years, from July 1944 to July 1971, nine of which she served in France, Germany, and Japan. During her career, Bailey advanced from a second lieutenant to colonel, the highest achievable military rank in the Nurse Corps. She set several landmarks for black nurses in US military, becoming the first black lieutenant colonel in 1964, the first black chief nurse in a mixed, non-segregated unit in 1966, and the first black full colonel in 1967.

During World War II, Bailey treated German prisoners of war. In the later years of her military career, she actively worked with minority organizations and advocated to increase black participation in the Corps. After her retirement from the Army, she served as a consultant to the Surgeon General in the Nixon administration, working to increase the number of minorities in the Nurse Corps. For many years, she made speeches supporting equal participation in United States Army across the United States.

Continue reading this article on Wikipedia.

Education

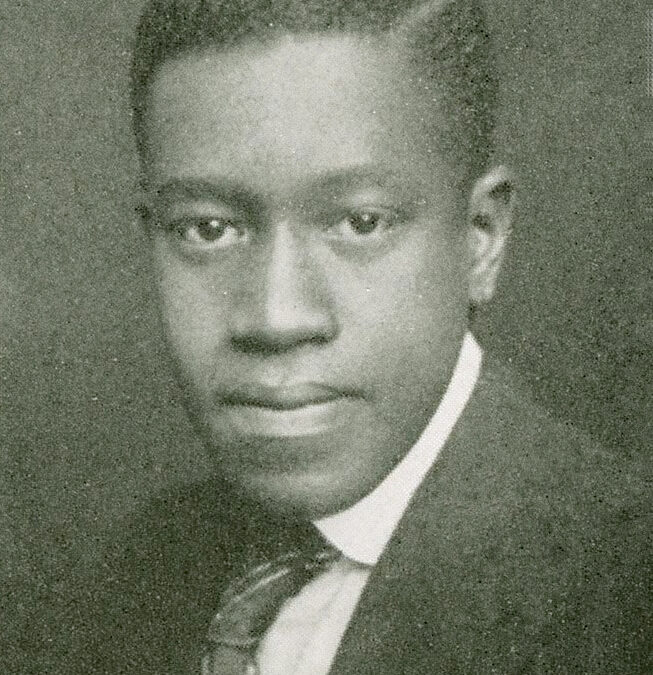

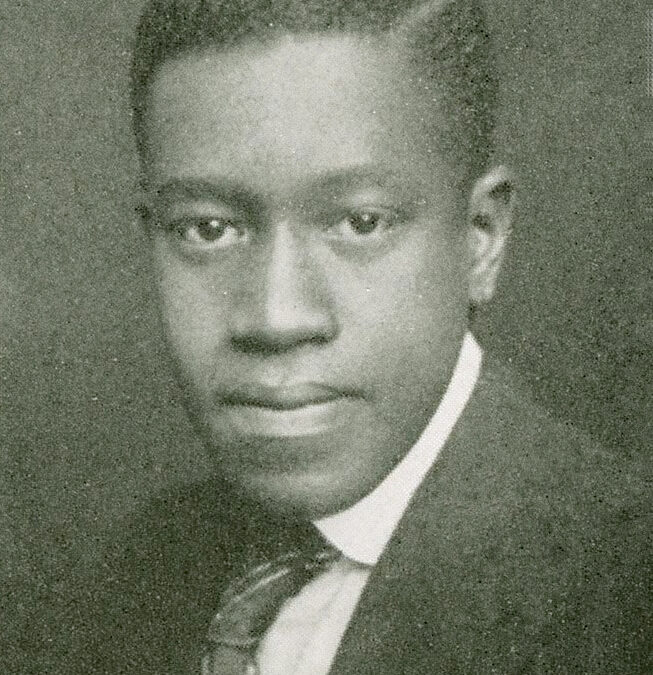

Elbert Frank Cox was born in Evansville, Indiana, in December 1895. He earned the baccalaureate degree from the University of Indiana in 1917 with a major in mathematics. After serving in the US Army in France during World War I, he returned to pursue a career in teaching. Before enrolling in the graduate mathematics program at Cornell University in September 1922, he taught mathematics in the public schools in Henderson, Kentucky and later at Shaw University in Raleigh, North Carolina. In 1925 he was awarded the Doctor of Philosophy degree in mathematics from Cornell and thus, he is the first known Black to receive the Ph.D. in Mathematics in the United States; in fact, in the world.

Cox’s thesis advisor was William Lloyd Garrison Williams, a McGill University mathematics professor from 1924-1952. Before arriving at McGill University, Williams taught at Cornell University, where he met Cox.; Despite having only a bachelor’s degree in mathematics, Cox had shown outstanding ability as an instructor at North Carolina’s Shaw University, thereby earning the Erastus Brooks Fellowship that allowed him to pursue his Ph.D. at Cornell. The two mathematicians became life-long friends and Williams arranged for Cox to come to Montreal for the final stages of his dissertation on the properties of difference equations.

When Williams realized that Cox had the chance to be recognized not only as the first Black in the United States, but as the first Black in the world to receive a Ph.D. in mathematics, he urged his student to send his thesis to a university in another country so that Cox’s status in this regard would not be disputed. Universities in England and Germany turned Cox down (possible for reasons of race), but Japan’s Imperial University of San Deigo accepted the dissertation.

In September 1925, Cox accepted a teaching position at West Virginia State College. He stayed there four year and in 1929 moved to Howard University. Cox remained at Howard until his retirement in 1965 and served as chairman of the Mathematics Department from 1957-1961. In 1975, the Howard University Mathematics Department, at the time of the inauguration of the Ph.D. program, established the Elbert F. Cox Scholarship Fund for undergraduate mathematics majors to encourage young Black students to study mathematics at the graduate level.

While Cox did not live to see the inauguration of the Ph.D. program at Howard, it is believed by many that Cox did much to make it possible. Cox helped to build up the department to the point that the Ph.D. program became a practical next step. He gave the department a great deal of credibility; primarily because of this personal prestige as a mathematician, as being the first Black to receive a Ph.D. in mathematics, because of the nature and kinds of appointments to the faculty that were made while he chaired the Department, and because of the kinds of students that he attracted to Howard to study mathematics at both the undergraduate and graduate (master’s) levels. Cox’s portrait hangs in Howard’s Mathematics Common Room as a reminder of his contribution to the Mathematics Department, the University, and the Community of scholars in general.

In 1980, the National Association of Mathematicians (NAM) honored Cox with the inauguration of the Cox-Talbot Address which is given annually at NAM’s National Meeting.

Education

Among the most outstanding African-American educators of the post-reconstruction era of the late nineteenth century to the middle of the twentieth century were Dr. Anna Julia Cooper and Ms. Nannie Helen Burroughs. During this extremely difficult and rocky period for African-Americans these dedicated sisters were confronted with the arduous tasks of struggling for racial uplift, economic justice and social equality.

Anna Julia Cooper (the eldest of the two women) was born Anna Julia Haywood on August 10, 1858 in Raleigh, North Carolina, the daughter of an enslaved African woman, Hannah Stanley, and her White master. From early on Cooper possessed an unrelenting passion for learning and a sincere conviction that Black women were equipped to follow intellectual pursuits. This thinking ran strongly against the popular opinion of the day. To the contrary, Cooper later said that “not far from kindergarten age” she decided to become a teacher. In Cooper’s words, speaking on the lack of the emphasis on formal education for Black girls, “Not the boys less, but the girls more.” In 1867 Cooper entered St. Augustine’s Normal School and Collegiate Institute in Raleigh. In 1925, at the age of sixty-seven, she earned a Ph.D. from Sorbonne University in Paris, France, becoming only the fourth African-American woman to obtain such a degree. At the tender age of 105, after a lifetime of educating African-American youth, Dr. Cooper died peacefully in her home in Washington, D.C.

Although exceptionally brilliant Anna Julie Cooper was not an isolated phenomenon. Nannie Helen Burroughs, another remarkable sister, was born on May 2, between 1879 to 1883 in Orange, Virginia, to John and Jennie Burroughs. Nannie Helen Burroughs, described as a “majestic, dark-skinned woman,” was only twenty-one years old when she became a national leader, catapulted to fame after presenting a dynamic speech entitled “How the Sisters are Hindered from Helping” at the annual conference of the National Baptist Convention in Richmond, Virginia in 1900.

Music

Eubie Blake, ragtime composer and performer, was born on February 7,1883 in Baltimore, Md. When he was around four or five, Blake began playing his family’s pump organ. Noticing his interest in music, Blake’s parents signed him up for piano lessons with a neighborhood teacher. In 1898, at the age of 15, Blake became interested in ragtime, to his mother’s dismay. Against her wishes and without her knowing, he began his professional music career by playing ragtime piano in Baltimore brothels, honky tonks and bars. He later played in clubs and saloons. Blake’s work led him to meet the major musicians of the time. One of whom, Noble Sissle, would later become his partner.

The pair met in 1915. Sissle joined Blake’s band as a singer. Noble Sissle and Eubie Blake created an vaudeville act, the Dixie Duo. They wrote songs and performed. Sophie Tucker sang their first song, “It’s all your fault.” The song was an instant hit. Then Blake and Sissle teamed up with another duo to create Shuffle Along The Broadway all-star cast included Josephine Baker Florence Mills and Paul Robeson. Many of Blake’s most famous songs come from Shuffle Along including “I’m Just Wild about Harry” and “Love Will Find a Way”. The play was so popular that in 1921 it was being performed by three different touring companies. After the success of Shuffle Along ,

Blake and Sissle collaborated on Elsie and Chocolat Dandies. Blake also created some shows on his own including Swing It, Blackbirds and Eubie! Then, as the popularity of ragtime faded, Eubie Blake took a twenty-three year break from show business. In 1969, at the age of 56 he returned. Blake toured the world playing piano and giving lectures on ragtime music. He made an album called The Fifty-six Years of Blake and he formed his own company. Just over one hundred years after his life began, on February 12, 1983, Eubie Blake died in Brooklyn, New York.

Slavery

Angelina Grimke, along with her sister Sarah, were the first women in the United States to publicly argue for the abolition of slavery. Cultured and well educated, Angelina had gone north from South Carolina with her sister with firsthand knowledge of the condition of the slaves. In 1836 Angelina wrote a lengthy address urging all women to actively work to free blacks. The sisters’ lectures elicited violent criticism because it was considered altogether improper for women to speak out on political issues. This made them acutely aware of their own oppression as women, which they soon began to address along with abolitionism. A severe split developed in the abolition movement, with some antislavery people arguing that it was the “Negro’s hour and women would have to wait.” The Grimkes refused to accept this idea, insisting on the importance of equality for both women and blacks. Angelina’s sister became a major theoretician of the women’s rights movement, challenging all the conventional beliefs about a woman’s place. As to men, she demanded: “All I ask of our brethren is that they will take their feet from off our necks.”

Politics

In 1950, Elizabeth Simpson Drewry became the first African- American woman elected to the West Virginia Legislature. She was born in Motley, Virginia, on September 22, 1893. She moved to McDowell County, West Virginia, as a small child and had a daughter at the age of fourteen. Her husband was Bluefield professor William H. Drewry, who died in Chicago in 1951.

Elizabeth Drewry began teaching in the black schools of coal camps along Elkhorn Creek in 1910, and later taught in the McDowell County black public school system. Drewry received her education at Bluefield Colored Institute, Wilberforce University, and the University of Cincinnati, and received a degree from Bluefield State College in 1933.

She first entered politics as a Republican precinct poll worker in 1921. In 1936, Drewry switched her party affiliation to Democrat and became involved in the state Federation of Teachers. She took an interest in local organizations such as the American Red Cross and the McDowell County Public Library. Drewry served on the Northfork Town Council and rose to the position of associate chairperson of the powerful McDowell County Democratic Executive Committee.

In 1948, she ran for the House of Delegates for the first time, but was defeated in the primary election by Harry Pauley of Iaeger. Five Democrats and five Republicans from McDowell County were elected in the primary to run in the general election. Since McDowell County was overwhelmingly Democratic, it virtually assured the five Democratic nominees of winning. Drewry was announced as the winner of the fifth spot on the Democratic ticket in the initial vote count, but Pauley protested the result. In a recount, 64 disputed ballots were all given to Pauley and he defeated Drewry by 32 votes.

In 1950, Drewry ran again and won the fifth spot on the Democratic ticket. In the general election, she received nearly 18,000 votes, becoming the first African-American woman elected to the legislature. In 1927, Minnie Buckingham Harper was appointed to succeed her late husband in the West Virginia Legislature, becoming the first black woman in the nation to serve in a state legislature. However, Harper was never elected.

During her thirteen years in the legislature, Drewry was a leading advocate for education and labor. She chaired both the Military Affairs and Health committees and served on the Judiciary, Education, Labor and Industry, Counties, Districts and Municipalities, Humane Institutions, and Mining committees. She introduced legislation in 1955 allowing women to serve on juries. West Virginia was the last state to eliminate this form of discrimination. In 1956, Ebony magazine honored Drewry as one of the ten outstanding black women in government. She retired due to poor health in 1964, having served longer in the legislature than any other McDowell Countian. Drewry died in Welch on September 24, 1979, at the age of eighty-five.