The “war between the states” would not be over for another year when Rachel Boone gave birth to John William Boone on May 17, 1864 at a federal army camp near Miami, Missouri. Rachel, a runaway slave owned by the decendants of pioneer Daniel Boone, had taken refuge with the regiment of the Union Army as a cook. The regiment’s bugler fathered the child, but they were never to know each other. Shortly after John William was born, Rachel moved to Warrensburg, Missouri where she earned a living by cleaning the homes of prominent families. At six months of age, the baby became very ill. The diagnosis was one for which there was no cure: “brain fever”. Only a very radical surgical procedure offered a chance to save the child’s life. His overall functioning might be saved if the pressure from the swelling from the swelling brain could to be lessened. There was one way to accomplish that ? by surgical removal of the eyes. The operation was performed. John William lost his sight ? but not his very considerable intelligence.

Greatly loved, John William is remembered as a very happy, musically gifted child. At age three, he was capable of beating out rhythms. He had a tin whistle at age five with which he could play tunes and immitate sounds in nature –like birds. Soon John organized a band with instruments that included tin whistle, drum, and tambourine. Rachel, who cherished her son, sought ways to have John educated. Impressively capable, she succeeded in recruiting the town’s assistance in her quest. Warrenberg’s city fathers purchased the railroad ticket that brought John William to the Missouri School for the Blind in St. Louis.

Well-received in the first year, John William attended the School for the Blind for two and one-half years. He quickly demonstrated his ability to reproduce on the piano any musical piece he heard. Despite his musical giftedness, the school was teaching him to make brooms. Driven to find outlets for his interests and talents, John would steal away to the ‘adult’ area of town to hear the good local piano playing. A Ragtime underground was beginning in St. Louis which allowed the child prodigy to experience ? and subsequently contribute to ? that very first truly American music. School officials finally penalized John’s truancy by expelling him from school. A conductor befriended the boy by allowing him to ride the train home in exchange for entertaining passengers by playing his harmonica.

In Warrensberg again, John lived in the Black community for the first time in his life. Rachel had married widower Harrison Hendrix, the father of five, when John was eight years old. Wanderlust gripped him, however, and he strayed from home repeatedly –at times, with regretable consequences. For example, John William was taken into bondage by a gambler, Mark Cromwell, who exploited him and treated him poorly. It was necessary for his stepfather –and later, ministers from the Missouri towns of Fayette and Glasgow– to rescue the young man.

The Christmas holidays of 1879 were to bring dramatic positive change to John’s life that would endure for all of his remaining years. The gifted young musician was invited to participate in a festival at the Second Baptist Church in Columbia. The event was an annual gift to the community by a very successful builder and contractor, John Lange, Jr. John William was a hit. He was invited back for a concert in March, 1880 –one in which he was featured with a second sightless Black pianist, Tom Bethune –known as ‘Blind Tom’. John William Boone’s professional career was launched with the event. John Lange, Jr. took on the role of his manager. It proved to be a superbly successful, profitable relationship.

Lange began by sending John William to Christian College in Columbia to further his musicianship. And, it was here that John was introduced to the European classical composers. Further, Lange’s organizational skills were outstanding. To transcend the stigma of disability, Lange adapted the motto, “Merit, not sympathy, wins” for the J. W. Boone Music Co. To make salient John William’s capacity to reproduce anything he heard, Lange made it known that one thousand dollars would be given to anyone who could stump Boone by playing something the artist could not play back exactly. Lange never had to make good on the offer. Lang also hired advance men, who would travel to towns to advertise Boone’s abilities and make the necessary arrangements prior to the arrival of the great man. These were the days when the piano for each concert had to be hauled in by horse and wagon –by the Boone Music Company.

The1880 Marshfield Tornado killed 105 people. As Lange read the account aloud, Boone composed the programmic piece – never notated. The piano roll machine broke down because it could not track so many notes. This piece became one of his ‘signature’ compositions and audiences loved to hear it because it replicated a natural disaster through music. His career peaked from 1885-1916. By 1885 the troupe earned $150 – $200 per night ? $600 on the best nights. His company was training ground for young singers. The best known was Melissa Fuell who would eventually write a biography of the company from its beginning until 1916. It was also training ground for advance agents ? men who went ahead to publicize and make arrangements.

By 1916, Boone was soo popular, he could not keep up with all of the requests for his performances. He toured US, Canada, and Mexico – and reportedly England, Scotland and Wales but no documentation has yet been found for the overseas events. John Lange wrote about the period from 1880 – 1915: a continuous period of 39-years, where they would travel 10 months each year, with 6 concerts per week ? a total of 8, 650 concerts. Distance traveled averaged 20 miles per day or 216,000 miles and they slept in 8,250 beds. Boone played mainly in churches and concert halls – and to segregated audiences. After he became popular, piano companies provided the pianos fo he did not have to haul them by horse and wagon. He wore out 16 pianos by 1915.

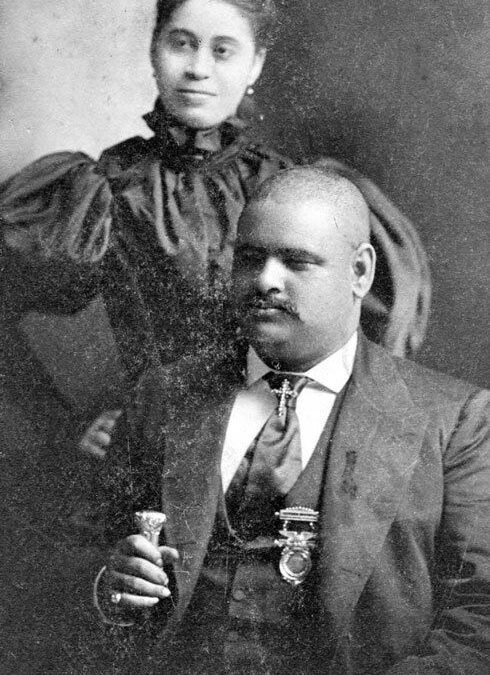

Fuell’s book documents the close and personal relationship between Boone and his manager. Boone married Lange’s youngest sister in 1889. Boone never recovered from Lange’s death in 1916; other managers were not as effective.

Besides a classical repetoir, Boone played plantation melodies, religious songs and Ragtime. He excited audiences about both realms of music and bridged the gap between classical and popular and also brought White and Black culture together by his appeal. He sang minstrel tunes/plantation songs. Wrote and sand ‘coon’ songs as all Black performers did that came out of the minstrel stereotypes of earlier years. Religious songs included “Nearer My God to Thee” and this has been preserved on piano roll. In 1912, he was contacted by the QRS Piano Roll Company and became one of the first Black artists to cut piano rolls. Boone did not receive very much royalty from the piano rolls. His Ragtime stuck very close to the origins of Ragtime –piecing together the Black folk songs into medleys as was typical of the early Ragtime period. We know that he was acquainted with some of classic Ragtime composers a newspaper article describes his visit to James Scott. Charlie Thompson of St. Louis played his “Lily Rag” for Boone. We know that he played the rags but he may have used the rags as encores. Concert programs do not list rags.

Boone gave generously to Black churches and schools ? and he used them for performances. He claimed to have put more roofs on churches in Columbia than anyone else. Because of this he had little estate –even though at one time he had had an income of $17,000 per year. He moved into a permanent home in Columbia when he married Eugenia Lange in 1889 which is now on the national register. Boone gave many benefit concerts to further Black schools and churches in the Columbia area.

He was just 5 feet tall but was a very impressive figure. Becasue he could not walk without guidance, he frequently carried a child upon his shoulders as a navigator. He had an astounding memory and was called a walking encyclopedia. He could remember people and tunes many years later ? i.e., 30 years after he had met someone or had played a tune. He could tell a child’s age by putting his hand upon a child’s head. Had a very happy and warm personality and children loved him ? and he they. He would tell them stories. He had a great big pocket watch with a chime effect ? children loved that. He belonged to fraternal organizations. His only family was his wife and his mother. His mother died in 1901.

Lange was the only person he could trust and depend upon. Boone never got over Lange’s death. After 1920, competition from movies and radio made it very difficult to secure bookings. So he did most of his work in small towns and public schools. The states he covered then were those adjacent of Missouri. He did a final big tour in the East in 1919 and 1920. Wayne Allen, a Columbia music publisher, unofficially became Boone’s manager in the 1920s but Allen really could not help Boone that much even though Allen promoted him greatly by writing letters to record companies. Boone almost recorded for the OK Record Co. but it did not materialize Other piano rolls were cut for the Vocal Style Co. in Cincinnati but these were apparently never issued.

After the 1919-1920 season, the tours declined. The routine $100 nights with Lange reduced to less than half that; he sometimes played for a flat fee of $40. But he remained optimistic. His last concert was on May 31, 1927. He died of a heart attack on October 4, 1927. The funeral was a major event in the Black community in Columbia. But the grave remained unmarked until 1971. He left little estate because he had sold some important real estate holdings. He used his house as a collateral for loans. One thing that did survive the ages was the “Big U”. The piano made for him specially by the Chickering Co. in 1891. The piano has been restored and is here in Columbia. There has been a revival of interest in Boone. In 1961, Blind Boone Memorial Foundation was formed. A concert was arranged to help stimulate more interest in Boone. TJT attended the concert at the Brewer Field House at the University on the 15th of March, 1961. The featured artist was Bob Darch. It was for this concert that Boone’s piano was fully restored. Despite the enthusiasm, the concert failed financially but the Boone County Sesquicentennial Commission of 1971 commemorated Boone and raised money for Boone’s grave and that of his wife Eugenia. In September,1960, the Boone County Housing Authority voted to designate the new federal public housing project in the Black community the John William Boone Housing Project. The Project contained a community center: the Blind Boone Center established in 1963. Boone County Historical Society acquired Maplewood, the former home of a prominent Columbia family for a museum and park –established the Blind Boone Room there with the piano; there’s a special events room at the University that bears his name. In 1980, five homes tied to Boone were put on the National Register of Historic Places ? including his home.