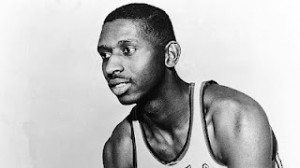

Lloyd started at power forward – with an emphasis on power – for the 1954-55 NBA champion Syracuse Nationals, who moved to Philadelphia in 1963 to become the 76ers. Lloyd now lives in a retirement community in Crossville, Tenn. He’s a major, if obscure, figure in NBA history.

He doesn’t mind his low profile. Lloyd has no interest in standing beside Robinson in the nation’s memory. Standing there would only make him nervous.

“If you could have lunch with anybody who ever lived on the earth, anybody in his right mind would have to pick lunch with Jesus Christ,� Lloyd says. “Man, I would love to pick his brain.

“But when you get back to mortals, my first pick would be Jackie Robinson. Just to talk a couple hours with him. Man, that would be sweet.�

Lloyd and the man he calls “my hero� would have plenty to talk about. Lloyd said he encountered virtually no racist treatment from his teammates and opponents during his decade (1950-60) in the NBA. He played in a brawling era, when basketball resembled the current-day NHL. Fights were common, and Lloyd never walked away from one, but he says the punches never were provoked by his race.

Fans of the 1950s were not so tolerant. The zenith of the Nationals era came in 1955, when Syracuse roared past the Fort Wayne Pistons for the NBA title. Nats players get a far-away look in their eyes when they talk of the victory.

Lloyd’s memories aren’t so sweet. He remembers harsh, cruel words. The Pistons played their home games in the title series in downtown Indianapolis, where the scene often grew ugly.

“Those fans in Indianapolis, they yell stuff like, ‘Go back to Africa.’ And I’m telling you, you would often hear the N-word. That was commonplace. There were a lot of people who sat close to you who gave you the blues, man.�

When clueless fans called Earl Lloyd names, he declined to respond. He wouldn’t even look at the faces of those who spewed hate. He used their idiocy to fuel his already considerable fire.

Lloyd was not the smoothest of players. He averaged more than 10 points per game in only one season. Instead, he earned his living by delivering basketball basics. He set bone-rattling, but clean, picks. He attacked the boards. He played rough, stingy defense. He was a starter on the Nats title team, a squad that resembled the Detroit Pistons of 2003-04, with its emphasis on defense.

He attacked the game and declined to worry about the dopes in the stands. When fans taunted him, he just tried harder to beat their team.

“My philosophy was if they weren’t calling you names, you weren’t doing anything,� Lloyd says. “You made sure they were calling you names, if you could. If they were calling you names, you were hurting them.�

Lloyd remains a keen observer of the NBA. He watches games, usually by himself, in his den. This pioneer usually enjoys the show.

“I like Shaquille O’Neal,� Lloyd says. “The guy plays hard. He’s unselfish. He’s a hell of a passer. He just a pro guy. I like the way he hurts people in the normal course of his job. He doesn’t go out of his way to hurt anybody, but when he goes to the basket, you got to be a brave man to get in his way.�

Lloyd led the way for O’Neal and so many others. When Lloyd was inducted into the Basketball Hall of Fame in 2002, he gave credit for his climb to his coaches, his parents, his friends, his wife, his teammates, and just about everyone except Earl Lloyd. That’s his nature.

Now, he often spends his afternoons relaxing in his den while listening to the wandering, wondrous jazz tunes of Miles Davis and John Coltrane. He thinks back to his ride through life and he’s filled with gratitude for those who boosted him. He sometimes sits in his den for eight hours straight, listening and thinking.

“I like being extremely retired,� he says.

He deserves an extreme boost in our collective memory.