Soon after Union troops had captured and occupied the southern city of Natchez, Mississippi, in the summer of 1863, northern missionaries set about establishing the region’s first schools for freedpeople. But they were surprised to learn that at least one school already existed, and it had been in operation for many years.

Soon after Union troops had captured and occupied the southern city of Natchez, Mississippi, in the summer of 1863, northern missionaries set about establishing the region’s first schools for freedpeople. But they were surprised to learn that at least one school already existed, and it had been in operation for many years.

Even more astounding, the students at this school were slaves and so was their teacher, Lily Ann Granderson. (Other sources identify her as Milla Granson and Lila Grandison.) Although a small number of slaves learned to read and write in the antebellum South, schools for slaves and slave teachers were extraordinarily uncommon.

Born into slavery in Virginia in 1816,

was of mixed parentage. Her mother was enslaved at age three after Lily Ann’s grandmother, a freeborn woman of Native American descent, died. All we know of her father is that he was from one of the First Families of Virginia (FFV), an exclusive group of elite whites that traced their descendants back to the first colonial settlers.

At some point in her childhood Lily Ann was moved to Kentucky. She worked as a house slave, and grew to know her master’s family quite well. The master’s children taught her how to read and write.

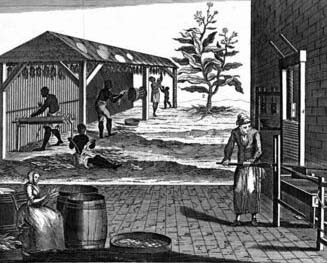

Whatever stability she knew in Kentucky was ruptured when her master died, and in the subsequent settling of the estate she was sold down the river to a Mississippi slaveholder. Compounding the shock of moving to the Deep South was the fact that she now had to work as a field hand on a cotton plantation. “O, how I longed to die!” she told a friend; “and sometimes I thought I would die from such cruel whippings upon my bared body.” [Haviland, 300] Under these conditions it did not take long for Lily Ann’s health to deteriorate. After much pleading, her master agreed to her request for a transfer to the kitchen, but for only part of the time.

Moving from the fields to town gave Lily Ann Granderson the opportunity to establish a night school for slaves. Beginning at eleven or twelve o’clock at night, slaves would sneak into a secluded room off of a back alley. All the doors and windows were shut tight, and the slave students used pitch-pine splinters to illuminate their writing instruments and reading materials. These precautions were necessary because state law forbid slave education. And masters feared–with good reason–that if even with a rudimentary education slaves would learn of abolitionism and figure out how to run away to the North. Lily Ann claimed that many of her students wrote their own passes and headed for Canada. Since these slaves were never heard from again, she surmised that they had successfully escaped to freedom.

For about seven years this little slave school operated under the noses of the authorities. Lily Ann took on twelve students at a time. After they had learned to read and write, she graduated them and accepted another twelve under her charge. All told, hundreds of slaves passed through her classroom. But word of the school’s existence eventually leaked out. Worried that her former students would be punished for their learning, Granderson was surprised to find out that the local authorities did not prosecute her or them. While the slave code prohibited whites from teaching slaves and free blacks from teaching slaves, apparently there was no law prohibiting a slave from teaching another slave. Emboldened by the positive turn of events, she opened a Sabbath school along with her midnight school.

In 1863 when federal soldiers and northern missionaries arrived in Natchez, they found an experienced slave teacher and quite a few literate slaves. The American Missionary Association added Lily Ann to their staff of teachers, and she continued to teach freedpeople for many years thereafter. In addition to her work in schools, she was involved in other community institutions; in particular she became a Deaconess in the local Baptist Church. The last we hear from Lily Ann Granderson is in 1870 when she opened a bank account at the newly established Freedmen’s Bank. She was 54 years old, still teaching in Natchez, married and with two children.

This biography was submitted by Justin Behrend, a Ph. D. Candidate in History at Northwestern University