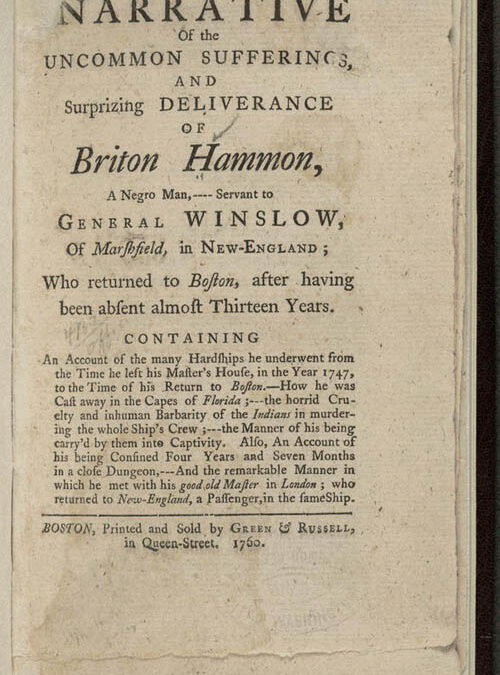

On a December day in 1747 Briton Hammon, a slave to Major John Winslow of Marshfield, Massachusetts, walked out of town with, as he put it, `an Intention to go a voyage to sea.’ Tucked into the sandy bight of Cape Cod Bay, some thirty miles south of Boston, and reeking of tidal flats and Stockholm tar, Marshfield was a minor star in the galaxy of Britain’s commercial empire, and only a short walk from Plymouth, where Hammon shipped himself the next day `on board of a Sloop, Capt. John Howland, Master, bound to Jamaica and the Bay’ of Campeche for logwood.

Experienced at shipboard work, as were approximately 25 percent of the male slaves in coastal Massachusetts during the 1740s, Hammon had not run away. But like all black people in early America who wrought freedom where they could, nurtured it warily, and understood it as partial and ambiguous at best, Hammon seized the moment. Prompted by memories of luxuriant Jamaican alternatives to sleety nor’easters, he negotiated the right for a voyage when his master Winslow’s frozen fields were untillable, and earned a brief sojourn in the black tropics — the productive heartland of the Anglo-American plantation system. Winslow, of course, pocketed most of the wages.