Black History, Civil Rights

The beginning of the desegregation of the Greyhound Bus Station waiting rooms in Louisville, KY, took place in 1953 and continued with the activism of Charles Ewbank Tucker, who was a minister, a civil rights activist, and an attorney. The actual challenge began in December of 1953 when William Woodsnell took a seat in the white waiting area of the Louisville Greyhound Bus Station and refused to move. Woodsnell was arrested and charged with disorderly conduct. The next day, Charles E. Tucker, Woodsnell’s attorney, took a seat in the white waiting area of the bus station and no one approached him or asked him to move. The Louisville Greyhound Bus Station was the starting point for segregated waiting rooms for passengers heading south aboard Greyhound buses. (more…)

The beginning of the desegregation of the Greyhound Bus Station waiting rooms in Louisville, KY, took place in 1953 and continued with the activism of Charles Ewbank Tucker, who was a minister, a civil rights activist, and an attorney. The actual challenge began in December of 1953 when William Woodsnell took a seat in the white waiting area of the Louisville Greyhound Bus Station and refused to move. Woodsnell was arrested and charged with disorderly conduct. The next day, Charles E. Tucker, Woodsnell’s attorney, took a seat in the white waiting area of the bus station and no one approached him or asked him to move. The Louisville Greyhound Bus Station was the starting point for segregated waiting rooms for passengers heading south aboard Greyhound buses. (more…)

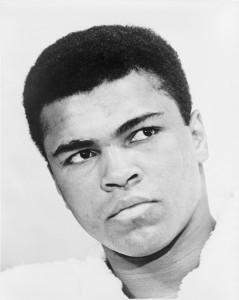

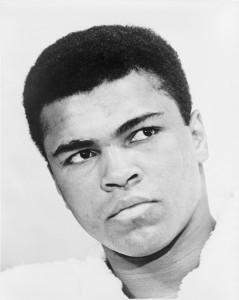

Black History, Civil Rights, Sports

Muhammad Ali

Muhammed Ali was born Cassius Clay in Louisville, Kentucky. From 1956-60, Clay fought as an amateur (winning 100 of 108 matches) before becoming the light-heavyweight gold medalist in the 1960 Olympics. Financed by a group of Louisville businessmen, he turned professional and by 1963 had won his first 19 fights. In 1964 he won the world heavyweight championship with a stunning defeat of Sonny Liston. Immediately afterwards, Clay announced that he was a Black Muslim and had changed his name to Muhammad Ali.

In 1967, after defending the championship nine times within two years, Ali was stripped of his title for refusing induction into the U.S. Army based on religious grounds. His action earned him both respect and anger from different quarters, but he did not box for three and one-half years until, in 1971, he lost to Joe Frazier.

A few months later, the U.S. Supreme Court affirmed his right to object to military service on religious grounds and Ali regained the title in 1974 by knocking out George Foreman in Zaire, Africa. Ali defended his title 10 times before losing to Leon Spinks in 1978. When he defeated Spinks later that same year, he became the first boxer ever to regain the championship twice. (more…)

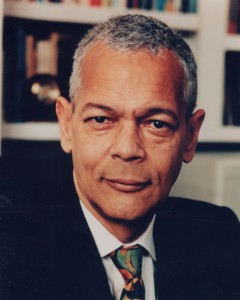

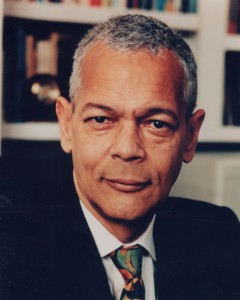

Black History, Civil Rights, Government, Politics

Julian Bond

HORACE JULIAN BOND (Jan. 14, 1940 – Aug. 15, 2015), U.S. legislator and black civil-rights leader, best known for his fight to take his duly elected seat in the Georgia House of Representatives. The son of prominent educators, Bond attended Morehouse College in Atlanta (B.A., 1971), where he helped found a civil-rights group and led a sit-in movement intended to desegregate Atlanta lunch counters.

In 1960 Bond joined in creating the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), and he later served as communications director for the group. In 1965 he won a seat in the Georgia state legislature, but his endorsement of a SNCC statement accusing the United States of violating international law in Vietnam prompted the legislature to refuse to admit him. (more…)

Black History, Civil Rights

Smith v. Allwright , 321 U.S. 649 (1944), was a landmark decision of the United States Supreme Court with regard to voting rights and, by extension, racial desegregation. It overturned the Texas state law that authorized the Democratic Party to set its internal rules, including the use of white primaries. The court ruled that the state had allowed discrimination to be practiced by delegating its authority to the Democratic Party. This affected all other states where the party used the rule.

Smith v. Allwright , 321 U.S. 649 (1944), was a landmark decision of the United States Supreme Court with regard to voting rights and, by extension, racial desegregation. It overturned the Texas state law that authorized the Democratic Party to set its internal rules, including the use of white primaries. The court ruled that the state had allowed discrimination to be practiced by delegating its authority to the Democratic Party. This affected all other states where the party used the rule.

The Democrats had excluded minority voter participation by this means, another device for legal disfranchisement of blacks across the South beginning in the late 19th century.

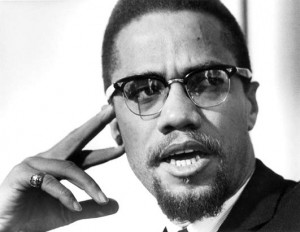

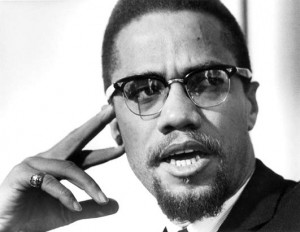

Black History, Civil Rights

Malcolm X

b.1925–d.1965. Born Malcolm Little in Omaha, NB, Malcolm was the son of a Baptist preacher who was a follower of Marcus Garvey. After the Ku Klux Klan made threats against his father, the family moved to Lansing, Michigan. There, in the face of similar threats, he continued to urge blacks to take control of their lives.

Malcolm’s father was slain by the Klan-like Black Legionaries. Although he was found with his head crushed on one side and almost severed from his body, it was claimed he had committed suicide, and the family was denied his death benefit. (more…)

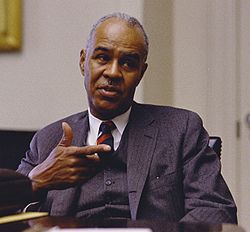

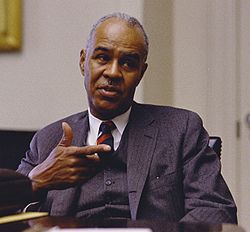

Black History, Civil Rights

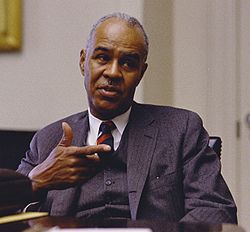

Roy Wilkins

Roy Wilkins (August 30, 1901 – September 8, 1981) was a prominent civil rights activist in the United States from the 1930s to the 1970s. Wilkins was active in the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and between 1931 and 1934 was assistant NAACP secretary under Walter Francis White. When W. E. B. Du Bois left the organization in 1934, Wilkins replaced him as editor of Crisis, the official magazine of the NAACP.

Roy Wilkins was born in St. Louis, Missouri. He grew up in the home of his aunt and uncle in a low-income, integrated community in St. Paul, Minnesota. Working his way through college at the University of Minnesota, Wilkins graduated from the University of Minnesota with a degree in sociology in 1923. (more…)

The beginning of the desegregation of the Greyhound Bus Station waiting rooms in Louisville, KY, took place in 1953 and continued with the activism of Charles Ewbank Tucker, who was a minister, a civil rights activist, and an attorney. The actual challenge began in December of 1953 when William Woodsnell took a seat in the white waiting area of the Louisville Greyhound Bus Station and refused to move. Woodsnell was arrested and charged with disorderly conduct. The next day, Charles E. Tucker, Woodsnell’s attorney, took a seat in the white waiting area of the bus station and no one approached him or asked him to move. The Louisville Greyhound Bus Station was the starting point for segregated waiting rooms for passengers heading south aboard Greyhound buses. (more…)

The beginning of the desegregation of the Greyhound Bus Station waiting rooms in Louisville, KY, took place in 1953 and continued with the activism of Charles Ewbank Tucker, who was a minister, a civil rights activist, and an attorney. The actual challenge began in December of 1953 when William Woodsnell took a seat in the white waiting area of the Louisville Greyhound Bus Station and refused to move. Woodsnell was arrested and charged with disorderly conduct. The next day, Charles E. Tucker, Woodsnell’s attorney, took a seat in the white waiting area of the bus station and no one approached him or asked him to move. The Louisville Greyhound Bus Station was the starting point for segregated waiting rooms for passengers heading south aboard Greyhound buses. (more…)