Black History, Military

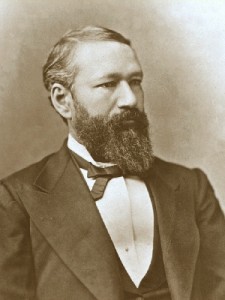

Pinckney Benton Stewart Pinchback

(b. May 10, 1837, Macon, Ga., U.S.–d. Dec. 21, 1921, Washington, D.C.), freeborn black who was a Union officer in the American Civil War and a leader in Louisiana politics during Reconstruction (1865-77).

Pinchback was one of 10 children born to a white Mississippi planter and a former slave–whom the father had freed before the boy’s birth. When the father died in 1848, the family fled to Ohio, fearing that white relatives might attempt to re-enslave them.

Pinchback found work as a cabin boy on a canal boat and worked his way up to steward on the steamboats plying the Mississippi, Missouri, and Red rivers. After war broke out between the states in 1861, he ran the Confederate blockade on the Mississippi to reach Federal-held New Orleans; there he raised a company of black volunteers for the North, called the Corps d’Afrique. When he encountered racial discrimination in the service, however, he resigned his captain’s commission. (more…)

Black History, Military

Milton L. Olive III

PFC Milton Olive III was only 18 at the time of his death in Vietnam, but his heroic acts were so great, that the City of Chicago has honored him in two ways. Chicago is home to Olive Park and Olive-Harvey College both named for this brave soldier.

PFC Olive belonged to the 3rd Platoon of Company B. As they moved through the Vietnam jungle to find the Viet Cong, Olive’s platoon was subject to heavy gunfire. Though pinned down temporarily, the unit retaliated by assaulting the Viet Cong positions.

While PFC Olive and four other soldiers were in pursuit, a grenade was thrown in their midst. PFC Olive saw the grenade, grabbed and put his body on it, absorbing the blast and saving the lives of the other soldiers in his platoon.

Black History, Military

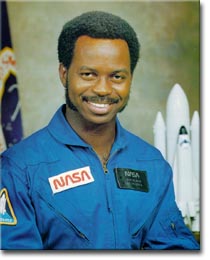

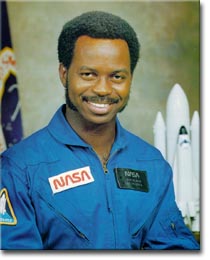

Ronald McNair

1950-1986 – On February 3, 1984, mission specialist Dr. Ronald McNair and his fellow crew members on space shuttle mission 41-B executed the first runway landing of the Challenger at Kennedy Space Center. McNair, a laser physicist, also played a key role in the mission’s other firsts: activating the Manned Maneuvering Unit; operating the Canadian Arm, which positioned crew members around the Challenger’s payload; and performing numerous mid-deck experiments.

In his “spare” time in space, McNair entertained the other four astronauts with a jazz concert on his saxophone�also a first in space. (more…)

Black History, Military

Crispus Attucks

A runaway slave who believed fiercely in freedom commanded the people of Boston “do not be afraid,” as he struck out against the redcoats and became the first hero to die in an attack that spurred the American Revolution.

On the night of March 5, 1770, five citizens of Boston died when eight British soldiers fired on a large and unruly crowd that was menacing them. Boston’s patriots, led by Sam Adams, immediately labeled the affray the Boston Massacre and hailed its victims as martyrs for liberty. The troops had been sent to Boston in late 1768 to support the civil authorities and were themselves subject to the jurisdiction of the local courts. (more…)

Black History, Military

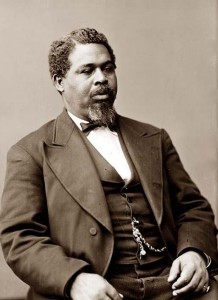

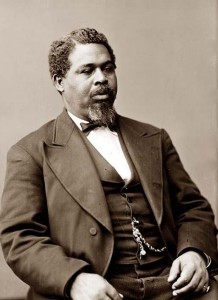

Robert Smalls

(b. April 5, 1839, Beaufort, S.C., U.S.–d. Feb. 22, 1915, Beaufort), Negro slave who became a naval hero for the Union in the American Civil War (1861-65) and went on to serve as a congressman from South Carolina during Reconstruction (1865-77).

The son of plantation slaves, Smalls was taken by his master in 1851 to Charleston, S.C., where he worked as a hotel waiter, hack driver, and rigger. Impressed into the Confederate Navy at the outbreak of the war, he was forced to serve as wheelman aboard the armed frigate “Planter.” On May 13, 1862, he and 12 other slaves seized control of the ship in Charleston harbour and succeeded in turning it over to a Union naval squadron blockading the city. This exploit brought Smalls great fame throughout the North. He continued to serve as a pilot on the “Planter” and became the ship’s captain in 1863. (more…)

Black History, Military

U.S.S. Mason

On March 20, 1944, at the Charleston shipyard in Boston, MA, the USS Mason was commissioned, or placed into active service, by the Governor of the state, the city’s mayor, and the ship’s new captain, William M. Blackford. The ship sailed for Belfast, Ireland, its first port of call, to join the British and American “Battle of the Atlantic.”

During W.W.II only one American Navy warship carried an African American crew into combat, The U.S.S. Mason. It was the job of smaller, easier to handle destroyer escort ships, like the USS Mason, to guard and protect the larger merchant vessels which carried badly needed supplies between the US and Europe. The mission of D. E?s was to stop German submarines, or U-boats, from sinking the larger ships with their deadly torpedoes. Although segregated on this one navel fighting ship, the men of the USS Mason were well-trained and bravely accepted and carried out the job they were given. (more…)