Salem Poor

A 28-year-old freedman who voluntarily enlisted, is said to have shot and killed British Lt. Col. James Abercrombie. Though 14 American officers sought Congress to bestow reward recognition to him, there is no record Congress ever did so.

A 28-year-old freedman who voluntarily enlisted, is said to have shot and killed British Lt. Col. James Abercrombie. Though 14 American officers sought Congress to bestow reward recognition to him, there is no record Congress ever did so.

A native of Georgia, Clarence Elder founded Elder Systems Incorporated, a research and development company located in Baltimore, Maryland. Elder developed Occustat, a monitoring and energy conservation system. Designed to reduce energy usage in buildings,

Occustat works by using a light beam aimed across building and room entrances to monitor traffic and, thus, occupancy. When the building or room is empty, heating, cooling, and lighting controls are lowered, reducing energy consumption by as much as 30 percent. Occustat is in use in hotels and schools. Elder, a graduate of Morgan State College, has also received 12 additional patents in the United States and abroad.

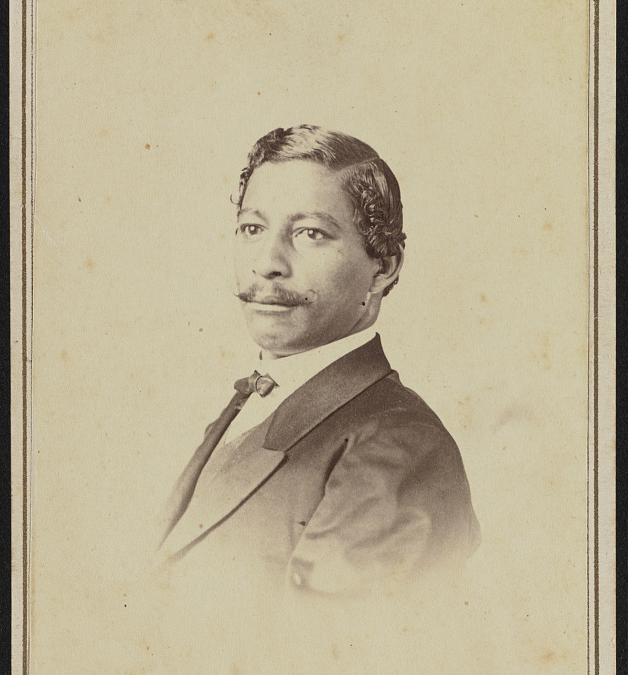

Charles Waddell Chesnutt (June 20, 1858 – November 15, 1932) was an American author, essayist, political activist, and lawyer, best known for his novels and short stories exploring complex issues of racial and social identity in the post-Civil War South. Two of his books were adapted as silent films in 1926 and 1927 by the African-American director and producer Oscar Micheaux. Following the Civil Rights Movement during the 20th century, interest in the works of Chesnutt was revived. Several of his books were published in new editions, and he received formal recognition. A commemorative stamp was printed in 2008.

During the early 20th century in Cleveland, Ohio, Chesnutt established what became a highly successful court reporting business, which provided his main income. He became active in the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, writing articles supporting education as well as legal challenges to discriminatory laws.

ogan, a free Black and soldier who fought in the Texas Revolution, was born into slavery about 1798 in Kentucky. He was emancipated by his White father, David Logan, and emigrated from Missouri to Texas in February 1831 to settle in Stephen F. Austin’s third colony. Logan was thirty-three years old when he arrived in Texas with his twenty-five-year-old wife Judah Duncan (ca. 1806–ca. 1832) and their five children. He obtained a Mexican land grant for a quarter of a league of land on Chocolate Bayou on December 22, 1831, in present-day Brazoria County and established himself as a blacksmith. Logan’s wife, Judah, and possibly all of their children apparently died shortly after their arrival. In 1832 Logan purchased a slave woman, Caroline Williamson (ca. 1802–ca. 1881), manumitted her, and then married her on December 30, 1833, in Brazoria County. It appears the couple had no children, since none were listed with them on the 1850 census. Furthermore, a petition filed by Caroline Logan in the 1870s indicated she was Greenbury Logan’s only heir, with the exception of Margaret J. Burgstrom (spelled Bergestone in the 1850 census), the orphan of a Swedish immigrant, whom the Logans adopted.

Logan, along with approximately 400 other free Blacks who had entered Texas by the mid-1830s, were afforded full citizenship rights by the Mexican government. Mexican law did not prohibit interracial marriages and made the territory attractive to mixed-race couples who wished to legalize their relationships. Despite the egalitarian environment of his newly-adopted country, Logan sided with the Texas colonists when conflict arose with the Mexican government.

Logan served at the battle of Velasco on June 26, 1832, and later, in 1835, answered the call for volunteers to march to Bexar. He joined Capt. James Walker Fannin’s company as a private in the middle of October and was with a detachment of approximately ninety men from Stephen F. Austin’s main force when they defeated a larger Mexican force near Mission Concepción (see BATTLE OF CONCEPCIÓN) on October 28, 1835. At the siege of Bexar, while he served in Capt. John York’s company, Logan volunteered to storm the works. He was wounded on December 5, 1835, the first day of action, when a ball passed through his right arm. Having “almost entirely lost the use of his right arm,” Logan was commended by the Texas legislature, which praised his conduct by declaring he had served “with distinguished alacrity.” At the age of thirty-eight, he was discharged from the army and opened a boarding house, tavern, and retail store in Brazoria with his wife.

The country’s regard for its Black patriots was short-lived. On January 5, 1836, the Texas legislature prohibited Blacks from entering the state, while granting temporary residency to those already there. Soon thereafter, the new constitution for the Republic of Texas was adopted and prohibited any person of color from residing in the republic without the consent of the legislature. On May 15, 1837, Logan petitioned the Texas Congress and stated that he “had hoped that after the zeal and patriotism” he had shown in “fighting for the liberty of his adopted Country,” he might be allowed to spend “the remainder of his days in quiet and peace,” but understood the constitution would not allow him to do so without the consent of the legislature. Acting upon his petition, the legislature recommended that Logan and his wife Caroline be “authorized to remain permanently and enjoy all the rights, priviliges [sic], and immunities of free Citizens.”

In June 1838, Logan received a bounty warrant for 320 acres for his service from October 4, 1835, to December 23, 1835, and a donation certificate for 640 acres for his service during the siege of Bexar. Logan penned a letter to his congressman, Robert Forbes, on November 22, 1841, informing him that he was in every fight during the campaign of 1835 and was the third man that fell when Bexar was taken. Logan complained to Forbes of his ill treatment by the government and that the constitution deprived him of “every previleg [sic] dear to a fre[e]man…no vote or say in [any] way.” Finding himself in an impoverished state, he sought a pension, in the form of a remission of taxes, in order to retain his property.

In 1860 Logan, his wife, and their adopted daughter Margaret were listed on the federal census as living in Fort Bend County. He was listed as a blacksmith with real estate valued at $2,500 and a personal estate valued at $3,000. His name was listed on Fort Bend County tax rolls in 1866. Greenbury Logan passed away about 1868, according to some genealogy sources, but the exact year of his death is unclear. He never attained the level of freedom he had enjoyed under Mexican rule some thirty years earlier. His frustration was evident in his petition to the legislature, just two short years after he had “shed his blood in a cause so glorious,” when he was forced to plead with the legislature for the “priviliges” of remaining in Texas. His widow, Caroline, lived out the remainder of her years with her adopted daughter, Margaret, who married William A. Taylor, in Fort Bend County, Texas, on September 10, 1863. On July 21, 1881, Caroline Logan received her last allotment of land for her husband’s service, 1,280 acres, which she sold the following month.

(b. April 3, 1838, Kaskaskia, Ill., U.S.–d. Oct. 8, 1893, Washington, D.C.), first black elected to the U.S. Congress, who was denied his seat by that body.

During the Civil War (1861-65) he served as a clerk in the U.S. Department of the Interior. In 1865 he moved to New Orleans, where he became active in the Republican Party, serving as inspector of customs and later as a commissioner of streets. He also published a newspaper,

The Free South, later named The Radical Standard. Elected to Congress from Louisiana in 1868 to fill an unexpired term, Menard failed to overcome an election challenge by the loser, and Congress refused to seat either man. In 1871 he moved to Florida, where he was again active in the Republican Party and published the Island City News in Jacksonville.

Ralph David Abernathy Sr. (March 11, 1926 – April 17, 1990) was an American civil rights activist and Baptist minister. He was ordained in the Baptist tradition in 1948. As a leader of the civil rights movement, he was a close friend and mentor of Martin Luther King Jr. He collaborated with King and E. D. Nixon to create the Montgomery Improvement Association, which led to the Montgomery bus boycott and co-created and was an executive board member of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). He became president of the SCLC following the assassination of King in 1968; he led the Poor People’s Campaign in Washington, D.C., as well as other marches and demonstrations for disenfranchised Americans. He also served as an advisory committee member of the Congress on Racial Equality (CORE).

In 1971, Abernathy addressed the United Nations speaking about world peace. He also assisted in brokering a deal between the FBI and American Indian Movement protestors during the Wounded Knee incident of 1973. He retired from his position as president of the SCLC in 1977 and became president emeritus. Later that year he unsuccessfully ran for the U.S. House of Representatives for the 5th district of Georgia. He later founded the Foundation for Economic Enterprises Development, and he testified before the U.S. Congress in support of extending the Voting Rights Act in 1982.

In 1989, Abernathy wrote And the Walls Came Tumbling Down, a controversial autobiography about his and King’s involvement in the civil rights movement. Abernathy eventually became less active in politics and returned to his work as a minister. He died of heart disease on April 17, 1990. His tombstone is engraved with the words “I tried”.