Black History, Civil Rights, Politics

Nelson Mandela

South Africa’s First Black President, Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela (7/18/1918 – 12/5/2013) was a South African anti-apartheid revolutionary, politician and philanthropist who served as President of South Africa from 1994 to 1999. He was the first black South African to hold the office, and the first elected in a fully representative election.

His government focused on dismantling the legacy of apartheid through tackling institutionalised racism, poverty and inequality, and fostering racial reconciliation. Politically an African nationalist and democratic socialist, he served as President of the African National Congress (ANC) from 1991 to 1997. Internationally, Mandela was Secretary General of the Non-Aligned Movement from 1998 to 1999. (more…)

Black History, Politics

Rosa Parks

Civil rights activist and reformer. Parks is best known for instigating the Montgomery bus boycott in 1955 in protest of segregation laws. Rosa Louise McCauley was born on February 4, 1913, in Tuskagee, Alabama. Her father, James, was a carpenter, and her mother, Leona, a teacher. Parks attended a liberal private school as an adolescent.

After briefly attending Alabama State University, she married Raymond Parks, a barber and activist, in 1932, and the couple settled in Montgomery, Alabama. Besides working as a seamstress and a housekeeper, Parks was involved in several African-American organizations. She served as secretary for her community chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, and also worked for the Montgomery Voters League, the NAACP Youth Council, and other civic and religious groups. (more…)

Black History, Firsts, Politics

Alexander Lucius Twilight is the first African American to graduate from a U.S. college, receiving his bachelor’s degree from Middlebury College in 1823. Also a pioneer in Vermont politics, Twilight became the first African American to win election to public office in 1836, joining his home-state legislature. He died in Brownington, Vermont, on June 19, 1857.

Alexander Lucius Twilight is the first African American to graduate from a U.S. college, receiving his bachelor’s degree from Middlebury College in 1823. Also a pioneer in Vermont politics, Twilight became the first African American to win election to public office in 1836, joining his home-state legislature. He died in Brownington, Vermont, on June 19, 1857.

Born on September 23, 1795 (though sources vary on the month and day of his birth, with some saying September 26 and others noting July 15), in Corinth, Vermont, where he also grew up, Alexander Lucius Twilight was one of six children born to Ichabod and Mary Twilight. The Twilights were one of the few African-American families living in the area at the time. According to the Old Stone House Museum’s website, Ichabod Twilight served in the American Revolutionary War. (more…)

Politics

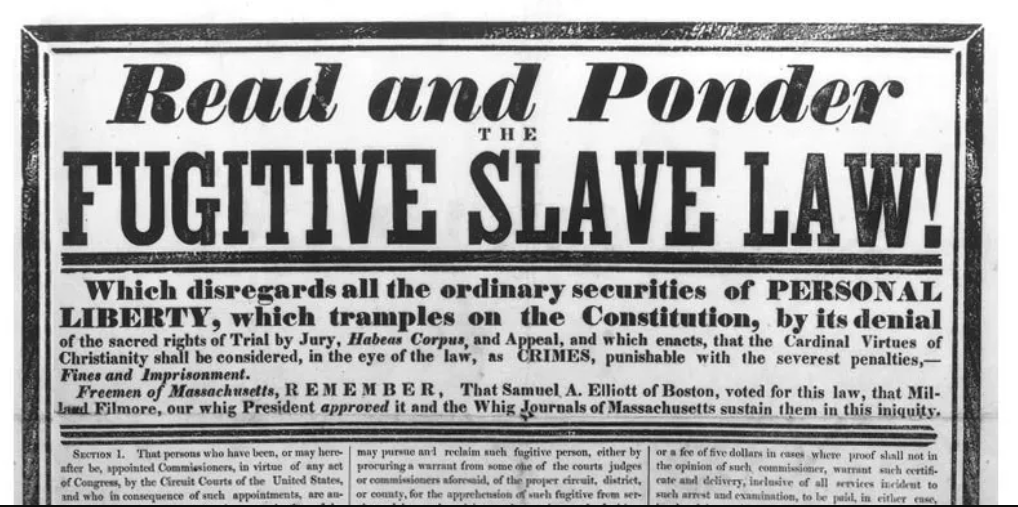

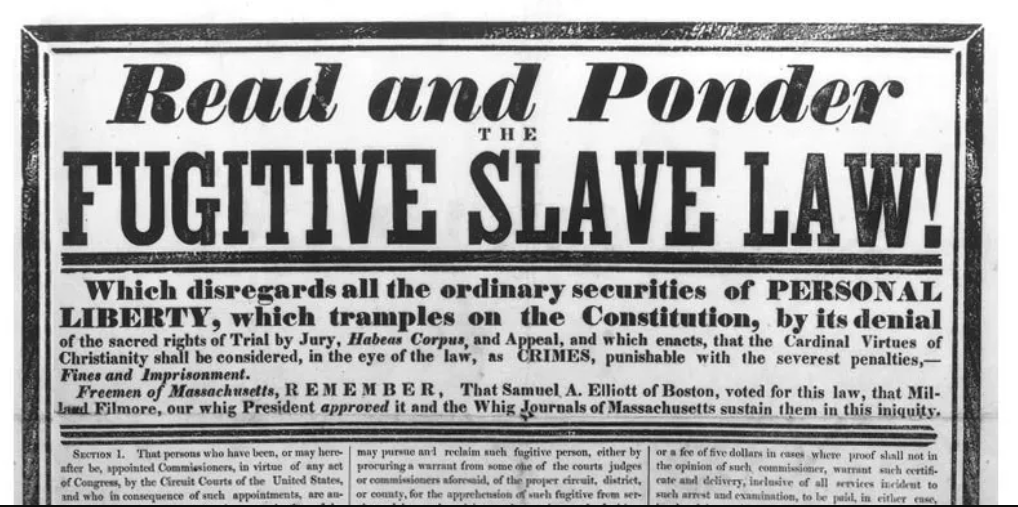

Following increased pressure from Southern politicians, Congress passed a revised Fugitive Slave Act in 1850.

Part of Henry Clay’s famed Compromise of 1850—a group of bills that helped quiet early calls for Southern secession—this new law forcibly compelled citizens to assist in the capture of runaways. It also denied enslaved people the right to a jury trial and increased the penalty for interfering with the rendition process to $1,000 and six months in jail.

In order to ensure the statute was enforced, the 1850 law also placed control of individual cases in the hands of federal commissioners. These agents were paid more for returning a suspected runaway than for freeing them, leading many to argue the law was biased in favor of Southern slaveholders.

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 was met with even more impassioned criticism and resistance than the earlier measure. States like Vermont and Wisconsin passed new measures intended to bypass and even nullify the law, and abolitionists redoubled their efforts to assist runaways.

The Underground Railroad reached its peak in the 1850s, with many enslaved people fleeing to Canada to escape U.S. jurisdiction.

Resistance also occasionally boiled over into riots and revolts. In 1851 a mob of antislavery activists rushed a Boston courthouse and forcibly liberated an escapee named Shadrach Minkins from federal custody. Similar rescues were later made in New York, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin.

Politics

In 1950, Elizabeth Simpson Drewry became the first African- American woman elected to the West Virginia Legislature. She was born in Motley, Virginia, on September 22, 1893. She moved to McDowell County, West Virginia, as a small child and had a daughter at the age of fourteen. Her husband was Bluefield professor William H. Drewry, who died in Chicago in 1951.

Elizabeth Drewry began teaching in the black schools of coal camps along Elkhorn Creek in 1910, and later taught in the McDowell County black public school system. Drewry received her education at Bluefield Colored Institute, Wilberforce University, and the University of Cincinnati, and received a degree from Bluefield State College in 1933.

She first entered politics as a Republican precinct poll worker in 1921. In 1936, Drewry switched her party affiliation to Democrat and became involved in the state Federation of Teachers. She took an interest in local organizations such as the American Red Cross and the McDowell County Public Library. Drewry served on the Northfork Town Council and rose to the position of associate chairperson of the powerful McDowell County Democratic Executive Committee.

In 1948, she ran for the House of Delegates for the first time, but was defeated in the primary election by Harry Pauley of Iaeger. Five Democrats and five Republicans from McDowell County were elected in the primary to run in the general election. Since McDowell County was overwhelmingly Democratic, it virtually assured the five Democratic nominees of winning. Drewry was announced as the winner of the fifth spot on the Democratic ticket in the initial vote count, but Pauley protested the result. In a recount, 64 disputed ballots were all given to Pauley and he defeated Drewry by 32 votes.

In 1950, Drewry ran again and won the fifth spot on the Democratic ticket. In the general election, she received nearly 18,000 votes, becoming the first African-American woman elected to the legislature. In 1927, Minnie Buckingham Harper was appointed to succeed her late husband in the West Virginia Legislature, becoming the first black woman in the nation to serve in a state legislature. However, Harper was never elected.

During her thirteen years in the legislature, Drewry was a leading advocate for education and labor. She chaired both the Military Affairs and Health committees and served on the Judiciary, Education, Labor and Industry, Counties, Districts and Municipalities, Humane Institutions, and Mining committees. She introduced legislation in 1955 allowing women to serve on juries. West Virginia was the last state to eliminate this form of discrimination. In 1956, Ebony magazine honored Drewry as one of the ten outstanding black women in government. She retired due to poor health in 1964, having served longer in the legislature than any other McDowell Countian. Drewry died in Welch on September 24, 1979, at the age of eighty-five.

Politics

(UNIA), primarily in the United States, organization founded by Marcus Garvey (q.v.), dedicated to racial pride, economic self-sufficiency, and the formation of an independent black nation in Africa. Though Garvey had founded the UNIA in Jamaica in 1914, its main influence was felt in the principal urban black neighbourhoods of the U.S. North after his arrival in Harlem, in New York City, in 1916.

Garvey had a strong appeal to poor blacks in urban ghettos, but most black leaders in the U.S. criticized him as an imposter, particularly after he announced, in New York, the founding of the Empire of Africa, with himself as provisional president. In turn, Garvey denounced the NAACP and many black leaders, asserting that they sought only assimilation into white society. Garvey’s leadership was cut short in 1923 when he was indicted and convicted of fraud in his handling of funds raised to establish a black steamship line. In 1927, President Calvin Coolidge pardoned Garvey but ordered him deported as an undesirable alien.

The UNIA never revived. Although the organization did not transport a single person to Africa, its influence reached multitudes on both sides of the Atlantic, and it proved to be a forerunner of black nationalism, which emerged in the U.S. after World War II.