Black History, Slavery

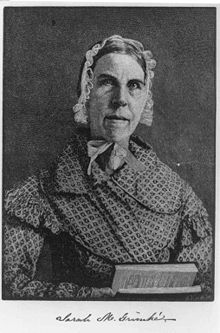

Sarah Moore Grimké

Sarah Grimke, along with her sister Angelina, were the first women in the United States to publicly argue for the abolition of slavery. Cultured and well educated, Sarah had gone north from South Carolina with her sister with firsthand knowledge of the condition of the slaves. In 1836 Angelina wrote a lengthy address urging all women to actively work to free blacks.

The sisters’ lectures elicited violent criticism because it was considered altogether improper for women to speak out on political issues. This made them acutely aware of their own oppression as women, which they soon began to address along with abolitionism. A severe split developed in the abolition movement, with some antislavery people arguing that it was the “Negro’s hour and women would have to wait.” (more…)

Black History, Other, Slavery

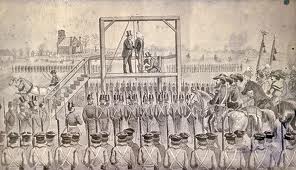

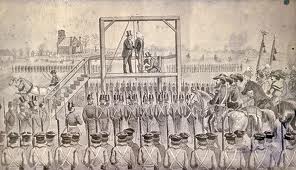

Nat Turner, the leader of a bloody slave revolt in Southampton County, Virginia, was hanged in Jerusalem, the county seat on November 11, 1831′

Turner, a slave and educated minister, believed that he was chosen by God to lead his people out of slavery. On August 21, 1831, he initiated his slave uprising by slaughtering Joseph Travis, his slave owner, and Travis’ family. With seven followers, Turner set off across the countryside, hoping to rally hundreds of slaves to join his insurrection. Turner planned to capture the county armory at Jerusalem, Virginia, and then march 30 miles to Dismal Swamp, where his rebels would be able to elude their pursuers. (more…)

Black History, Slavery

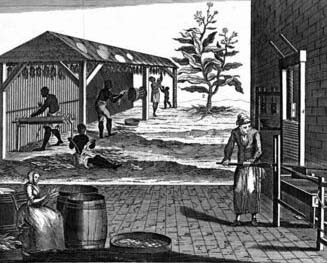

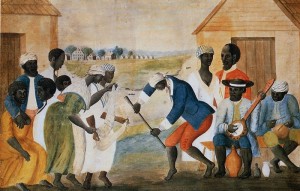

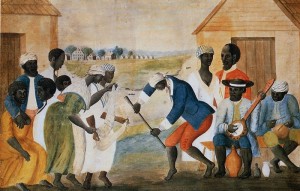

In 1654, John Casor became the first legal slave in America. Anthony Johnson, previously an African indentured slave, claimed John Casor as his slave. The Northampton County rule against Casor, and declared him propter for life by Anthony Johnson. Since Africans were not English, they were not covered by the English Common Law.

In 1654, John Casor became the first legal slave in America. Anthony Johnson, previously an African indentured slave, claimed John Casor as his slave. The Northampton County rule against Casor, and declared him propter for life by Anthony Johnson. Since Africans were not English, they were not covered by the English Common Law.

The First Black Slave was brought by the Dutch to the colony of Jamestown, 1619.

Black History, Education, Slavery

Soon after Union troops had captured and occupied the southern city of Natchez, Mississippi, in the summer of 1863, northern missionaries set about establishing the region’s first schools for freedpeople. But they were surprised to learn that at least one school already existed, and it had been in operation for many years.

Soon after Union troops had captured and occupied the southern city of Natchez, Mississippi, in the summer of 1863, northern missionaries set about establishing the region’s first schools for freedpeople. But they were surprised to learn that at least one school already existed, and it had been in operation for many years.

Even more astounding, the students at this school were slaves and so was their teacher, Lily Ann Granderson. (Other sources identify her as Milla Granson and Lila Grandison.) Although a small number of slaves learned to read and write in the antebellum South, schools for slaves and slave teachers were extraordinarily uncommon. (more…)

Black History, Slavery

Newspaper Report Of The Charles Deslondes Revolt Of 1811:

Charles Deslondes

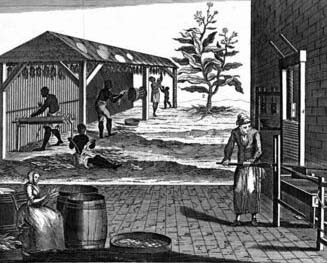

In 1811, another “largest slave revolt in American history” took place in New Orleans, Louisiana. During this revolt about 500 enslaved Africans, armed with pikes, hoes, axes and a few firearms, marched on the city of New Orleans with flags flying and drums beating. Many of the slaves had participated in the Haitian Revolution. This revolt was led by Charles Deslondes, a mulatto from Saint Dominique, Haiti. They were well-organized and used military formation dividing themselves into companies commanded by various officers. They showed a variety of military formations, but collapsed in combat against a well- armed militia and regular army troops under General Wade Hampton.

The events were as followed. On January 8, 1811 the rebellion began late in the evening on the plantation of Colonel Manuel Andy located in the German Coast County, some thirty-six miles northwest of New Orleans near present-day Norco. According to contemporary sources the leader of the revolt was a mulatto “a yellow fellow,â€� probably of Santo Domigan or Jamaican origin. He was the property of the Widow Jean–Baptiste Deslondes at the time of the uprising. Charles Deslondes was in the temporary employment of Colonel Andry or Andre, the sources use alternate spellings of his name. (more…)

Black History, Law, Slavery

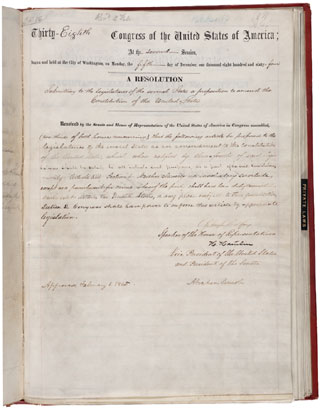

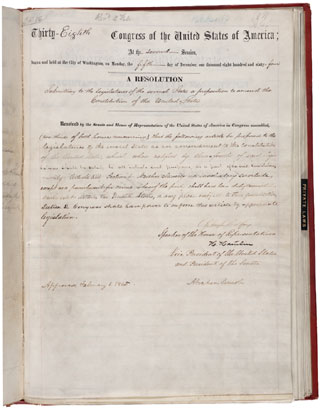

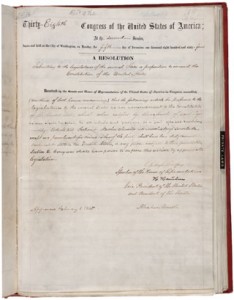

Passed by Congress on January 31, 1865, and ratified on December 6, 1865, the 13th amendment abolished slavery in the United States.

Passed by Congress on January 31, 1865, and ratified on December 6, 1865, the 13th amendment abolished slavery in the United States.

AMENDMENT XIII

SECTION 1.

Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.

SECTION 2.

Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.

In 1654, John Casor became the first legal slave in America. Anthony Johnson, previously an African indentured slave, claimed John Casor as his slave. The Northampton County rule against Casor, and declared him propter for life by Anthony Johnson. Since Africans were not English, they were not covered by the English Common Law.

In 1654, John Casor became the first legal slave in America. Anthony Johnson, previously an African indentured slave, claimed John Casor as his slave. The Northampton County rule against Casor, and declared him propter for life by Anthony Johnson. Since Africans were not English, they were not covered by the English Common Law.