Black History, Firsts, Sports

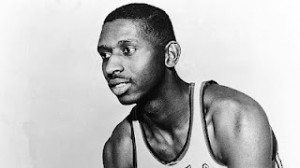

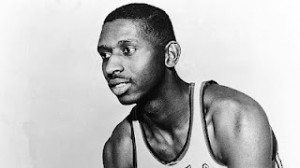

Earl Lloyd

Jackie Robinson, the man who broke Major League Baseball’s color line, ranks as a national icon. Filmmaker Ken Burns go so far as to compare Robinson to Thomas Jefferson. Earl Lloyd, the first African-American to play in the National Basketball Association, ranks as a largely overlooked pioneer.

Lloyd started at power forward – with an emphasis on power – for the 1954-55 NBA champion Syracuse Nationals, who moved to Philadelphia in 1963 to become the 76ers. Lloyd now lives in a retirement community in Crossville, Tenn. He’s a major, if obscure, figure in NBA history.

He doesn’t mind his low profile. Lloyd has no interest in standing beside Robinson in the nation’s memory. Standing there would only make him nervous. (more…)

Black History, Sports

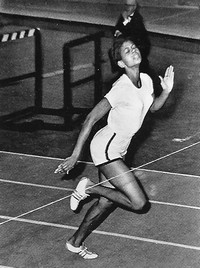

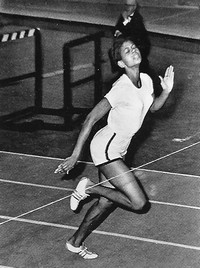

Wilma Rudolph

1940-1994 Born in St. Bethlehem, Tennessee, Wilma Rudolph was the first female American runner to win three gold medals in the Olympic Games. She earned the title of “World’s Fastest Woman” by winning the 100-meter dash and the 200-meter dash and anchoring the 400-meter relay at the 1960 Olympics in Rome.

These achievements would be considered remarkable by any standard, but in light of the fact that as a child Rudolph suffered an attack of polio and scarlet fever that left her unable to walk without braces or orthopedic shoes until age twelve, they are amazing. Rudolph’s phenomenal accomplishments helped remove barriers to women’s participation in track and field events. (more…)

Black History, Sports

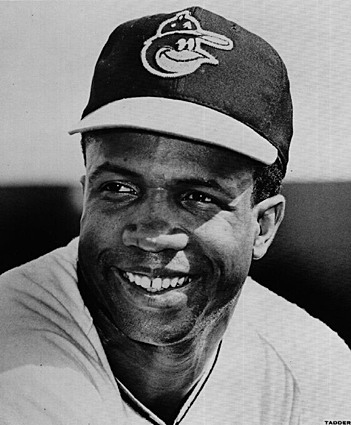

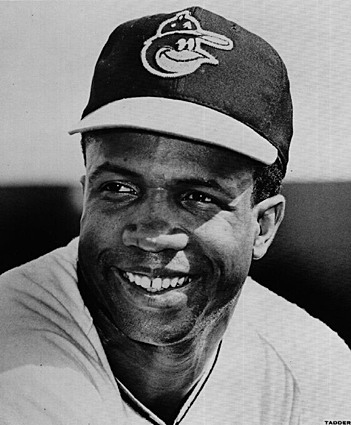

- Josh Gibson

Elected to Major League Baseball Hall of Fame in 1972.

Among the biggest draws in the Negro Leagues, popular Josh Gibson is generally considered one of the most prodigious power hitters in the history of professional baseball. Josh led the Negro National League in home runs for 10 consecutive years; credited with 75 home runs in 1931.

Belting home runs of more than 500 feet was not unusual for Gibson. One homer in Monessen, Pa., reportedly was measured at 575 feet. The Sporting News of June 3, 1967 credits Gibson with a home run in a Negro League game at Yankee Stadium that struck two feet from the top of the wall circling the center field bleachers, about 580 feet from home plate.

Although it has never been conclusively proven, Chicago American Giants infielder Jack Marshall said Gibson slugged one over the third deck next to the left field bullpen in 1934 for the only fair ball hit out of the House That Ruth Built. (more…)

Black History, Sports

Frederick Douglass “Fritz” Pollard

Frederick Douglass “Fritz” Pollard (January 27, 1894 – May 11, 1986) was the first African American head coach in the National Football League (NFL). Pollard along with Bobby Marshall were the first two African American players in the NFL in 1920. Sportswriter Walter Camp ranked Pollard as “one of the greatest runners these eyes have ever seen.”

Pollard was born in Chicago on January 27, 1894. He attended Lane Tech High School where he played football, baseball, and ran track. Pollard attended Brown University, majoring in chemistry. Pollard played half-back on the Brown football team, which went to the 1916 Rose Bowl. He became the first black to be named to the Walter Camp All-America team.

He later played pro football with the Akron Pros, the team he would lead to the NFL (APFA) championship in 1920. In 1921, he became the co-head coach of the Akron Pros, while still maintaining his roster position as running back. He also played for the Milwaukee Badgers, Hammond Pros, Gilberton Cadamounts, Union Club of Phoenixville and Providence Steam Roller. Some sources indicate that Pollard also served as co-coach of the Milwaukee Badgers with Budge Garrett for part of the 1922 season. He also coached the Gilberton Cadamounts, a non-NFL team. In 1923 and 1924, he served as head coach for the Hammond Pros. (more…)

Black History, Sports

William Eldon ‘Willie’ O’Ree

While Willie O’Ree career was short, it was historic. Willie became the first black player in NHL history on January 18, 1958, when he debuted with the Bruins in a 3-0 win over Montreal in the Forum. Willie was a skater, but only managed 45 games in the NHL, although he played professional hockey until 1971, mostly in San Deigo, California, where upon his retirement he became director of Parks with the City of San Deigo.

Another strike against Willie was an accident playing hockey as a junior in Kingston had left him blind in one eye. Willie played professionally in the Quebec Senior League, with another, Fredericton native, Manny McIntrye. Manny along with brothers Herb and Ossie Carnegie of Toronto, formed what is believed to be the only All-Black line in Professional hockey.

Black History, Sports

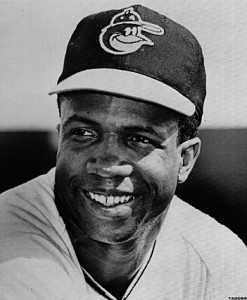

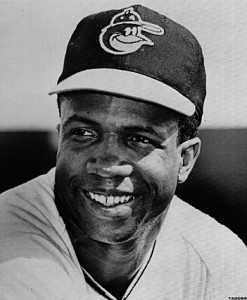

Frank Robinson

Frank Robinson played for the Orioles from 1966-1971 and in his first season with the Orioles, Robinson won the triple crown and the American League MVP award, becoming the only player to win the award in both leagues. He was also a memeber of the 1966 and 1970 World Series championship teams.

Robinson returned to Baltimore as the team’s manager from 1988-1991, and was named the American League Manager of the Year in 1989. His No. 20 jersey was retired by the Orioles in 1972 and he was elected into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1982.

He finished his career a .294 lifetime hitter with 586 home runs and 1,812 RBIs. (Baltimore Sun / July 15, 1968)