The Secretary of the Navy Authorized enlistment of slaves as Union sailors, September 25, 1861

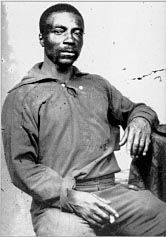

The Union Navy began to employ African American men on board ships as crew members and sailors very early in the war. And as the war progressed, blockading squadrons and naval vessels also took on board numerous “contraband” slaves who managed to escape from land to sea.

By 1863, the Union navy was enlisting and actively recruiting runaway slaves as crewmembers or paid sailors, usually at the low rank of “landsman.” By the end of the war nearly 20,000 black sailors had enlisted, a figure which represented nearly 20 percent of the navy’s enlisted men. The majority of these black sailors were men who had been enslaved but seized naval service as a route to freedom.

A few of the thousands of “contraband” slaves who became sailors were present at the battles of Galveston and Sabine Pass in 1863. Both battles demonstrated the unique dangers that African American men faced when they participated in combat operations against the Confederacy. One “escaped slave” participated in the Battle of Galveston of January 1, 1863, before being captured and marched to Houston, and according to a newspaper report at the time, the crowds who gathered in the city to watch the parade of federal prisoners from the U.S.S. Harriet Lane down Main Street jeered at and paid special attention to one of the “negroes” who was “clothed in sailor’s uniform”

But African American men who became Union sailors risked more than just ridicule if they were captured by Confederate forces. The diary of Union prisoner of war Alexander Hobbs, who was also captured from the U.S.S. Harriet Lane, reported on January 15, 1863, that “six coulered men” from aboard his ship–all “but one or two … free born”–were to be “sold togather”

Contemporary records show that “six Negroes claiming to be free” from aboard the Harriet Lane were in fact forced into labor at the Texas State Penitentiary in Huntsville, confirming the outlines of Hobbs’s story. Whether they ever escaped the penitentiary, even after war’s end, is difficult to tell.