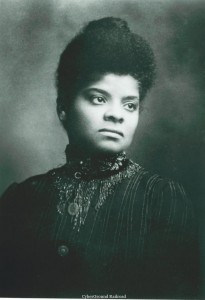

b.1862 – d.1931. Anti-lynching crusader, journalist, and advocate for racial justice and women’s suffrage. For Wells-Barnett, overcoming racism and halting the violent murder of black men was a central mission among her wide-ranging struggles for justice and human dignity. Born in Mississippi, she was educated at Rust University, actually a high school and industrial school. From 1884 to 1891, she taught in a rural school near Memphis and attended summer classes at Fisk University in Nashville.

A pattern of resistance to racial subordination was set early in Wells’ life. In 1887, she purchased a railroad ticket in Memphis and took a seat in the section reserved for whites. When she refused to move, she was physically thrown off the train. She successfully sued the Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad for damages. Upon appeal, however, the Supreme Court of Tennessee reversed the lower court’s ruling.

In 1891, Wells-Barnett co-founded the militant newspaper, Free Speech, in Memphis. She wrote scathing editorials denouncing local whites for lynching black men ostensibly to protect the sanctity of white womanhood but actually to eliminate them as economic competitors. Her pieces provoked a mob to burn her press while she was on a lecture trip to Philadelphia and New York. With a death threat hanging over her in Memphis, Wells-Barnett decided to remain in the North. During her exile, she wrote the pamphlet A Red Record (1895), a statistical account and analysis of three years of lynchings.

Wells-Barnett then launched an international crusade against lynching. She lectured in England in 1893 and 1894. She implored churches and organizations like the Young Women’s Christian Association and the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union to lend support. In 1895, she married Ferdinand Lee Barnett, lawyer and editor of the Chicago Conservator. They raised four children, and she adeptly managed career, marriage, motherhood, and social protest work.

Given the fervor of her determination to end racial discrimination and sexual inequality, it is not surprising that Wells-Barnett played a pivotal role in the development of a local and national network of black women’s clubs. President of the Ida B. Wells Club and founder of the Negro Fellowship League and the Alpha Suffrage Club of Chicago, Wells-Barnett greatly influenced black life during the Progressive Era. She worked with Jane Addams to block the establishment of segregated public schools in Chicago and served as probation officer from 1913 to 1917 for the Chicago municipal court.

When the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) was formed in 1909, Wells-Barnett insisted that the leadership take an unwavering stand against lynching and, years later, withdrew when the organization’s leadership failed to adopt the militant posture she advocated. She was also unable to persuade leaders in the women’s suffrage movement to speak out against racism and denounce lynching. The young white leaders of the National American Woman Suffrage Association–especially its southern members–feared that too close an association with black issues would jeopardize their cause. It would not be until 1930, the year before Wells-Barnett’s death, that black and white women joined forces to launch the Association of Southern Women for the Prevention of Lynching.