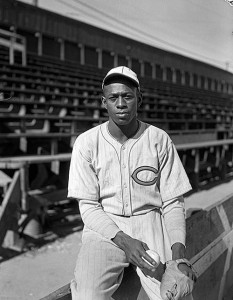

Regarded as the nearest thing to a legend that ever came out of the Negro Leagues, this tall, lanky right-hander parlayed a pea-sized fastball, nimble wit, and a colorful personality into a household name that is recognized by people who know little about baseball itself and even less about the players who performed in the Jim Crow era of organized baseball. His name has become synonymous with the barnstorming exhibitions played between traveling black teams and their white counterparts.

A mixture of fact and embellishment, Satchel’s stories are legion and form a rich array of often-repeated folklore. On many occasions he would pull in the outfielders to sit behind the mound while he proceeded to strike out the side with the tying run on base. Once he intentionally walked Howard Easterling and Buck Leonard to load the bases so he could pitch to Josh Gibson, the most dangerous hitter in black baseball, and then struck him out. He was advertised as guaranteed to strike out the first nine batters he faced in exhibition games, and he almost invariably fulfilled his billing.

Satchel frequently warmed up by throwing twenty straight pitches across a chewing gum wrapper that was being used for home plate. His “small” fastball was described by some hitters as looking like a half dollar. Others said that he wound up with a pumpkin and threw a pea. But Biz Mackey had the best story about how small his fastball looked. He said that once Satchel threw the ball so hard that the ball disappeared before it reached the catcher’s mitt. The stories are endless. But the facts are also impressive.

His generally accepted birth date is July 7, 1906, in Mobile, Alabama, but no one really knows the true date, and Satchel maintained an air of mystery about his age throughout his career. The only certainty about his birth is that it was sometime in the 20th century. As one of a dozen children, he learned early to fend for himself. He rarely attended school and frequently got into mischief.

When he was a youngster he carried suitcases at the train station for tips. Once he attempted to steal a man’s satchel but the owner ran him down and cuffed him about the head while recovering his property. A friend who witnessed the incident gave him the nickname “Satchel,” which young LeRoy hated. In later years he concocted various versions of the origin of his nickname that were more socially acceptable.

Later he was caught stealing costume jewelry and was sent to Mount Meigs reform school, where he converted his natural ability into a measure of pitching polish. After leaving Mount Meigs he pitched for the Mobile Tigers and other local semi-pro teams for a couple of years before embarking on his professional career in 1926 with Chattanooga in the Negro Southern League. After arriving in Chattanooga he was described as “just a big ol’ tall boy” who had extraordinary speed but was lacking the fine control that he developed later in his career. He joined the Birmingham Black Barons of the Negro National League in 1927, where he fashioned an 8-3 record, and soon thereafter established himself as a gate attraction and began playing year-round. While with the Black Barons he finished seasons of 10-11 and 10-4 in 1929-1930.

In 1931 he joined Tom Wilson’s Nashville Elite Giants when they moved to Cleveland to play as the Cleveland Cubs, but before the season was over he had been persuaded by Gus Greenlee to sign with his newly acquired ballclub, the Pittsburgh Crawfords. In the latter part of June he pitched the first victory for the Crawfords over the Homestead Grays, winning a close 6-5 contest. Paige’s greatest popularity came through this association with the Pittsburgh Crawfords during the early 1930s. He compiled marks of 32-7 and 31-4 in 1932-1933. In 1934 he was credited with a league record of 10-1. That season he and Slim Jones matched up in Yankee Stadium in what is considered the greatest game ever played in Negro Leagues history. The game, ended by darkness after 10 innings, was a 1-1 tie. As a result of Paige’s relationship with Greenlee, his stay with the Crawfords was interrupted with frequent salary disputes leading to intervals when Satchel pitched in Bismarck, North Dakota, with a white semi-pro team. He is credited with winning 134 of 150 games pitched with Bismarck and, while in the Midwest, he pitched on occasions with the Kansas City Monarchs, including an October exhibition game victory over Detroit Tiger ace Schoolboy Rowe and a team of major-leaguers. After returning to the Pittsburgh Crawfords in 1936, he is credited with a 24-3 record.

In the spring of 1937 he jumped to the Dominican Republic, where he pitched the Ciudad Trujillo team to a championship. He topped the league in wins, with a 8-2 record in the 31-game season. When he returned to the United States, he was banned by the Negro National League, so he formed his own team and toured across the country for the remainder of the season, outdrawing the league teams. In 1938 his contract was sold to the Newark Eagles, but although he was on the roster, he never actually participated in a game with them. Unable to reach accord in his negotiations with Effa Manley, he went to Mexico, but developed a sore arm, and the experts predicted that he was washed up.

Needing a job, Satchel signed with J.L. Wilkinson to play on the Kansas City Monarchs’ traveling team as a gate attraction, but unexpectedly, his arm “came back,” and he also developed a curve and his famous hesitation pitch to add to his “bee ball,” “jump ball,” “trouble ball,” “long ball,” and the other pitches in his repertory.

He joined the Monarchs’ league team during the latter part of the 1939 season, and for the next decade he pitched for them, pitching them to four consecutive Negro American League pennants (1939-1942), culminating in a clean sweep of the powerful Homestead Grays in the 1942 World Series, with Satchel himself winning 3 of the games. During the regular season of 1942 he posted a 9-5 record, after having finished undefeated in league play with a 6-0 ledger the previous year.

After many key players were drafted, the Monarchs’ baseball fortunes fell on leaner times, and Paige dropped to an 8-10 record in 1943. During the next two seasons he pitched more exhibition games than league contests, often with other teams. In 1944 he pitched in only 8 league games, posting a 4-2 record with a 0.75 ERA, and the following season he was still an effective worker on the mound and knew “all the tricks of his trade” but was “on loan” most of the year and infrequently pitched in league games.

In 1946, with the key starters back in the Kansas City fold, he helped pitch the Monarchs to their fifth pennant during his tenure with the team, but during the ensuing World Series against the Newark Eagles he missed the last 3 games, reportedly to make arrangements to play in a Caribbean winter league, and the Monarchs lost the Series in 7 games. In addition to the 2 Negro World Series, during his career in the Negro Leagues Paige also pitched in 5 East-West All Star games, being credited with 2 victories in the midseason classic.

Like most pitchers, Paige thought he was a good hitter, but he was really a relatively weak hitter and only an average fielder. However, sometimes in the Caribbean winter leagues he would play at first base, and he acquitted himself there adequately. In the 1939-1940 Puerto Rican winter league with Guayama, he led the team to the pennant with a performance that produced statistics that included a 19-3 record for a .864 winning percentage, and a 1.93 ERA with 208 strikeouts in 205 innings pitched and 6 shutouts in 24 games. His only other year in Puerto Rico was in 1947-1948.

Other winters he pitched in the California winter league with teams including the Royal Giants and the Baltimore Giants. Joe DiMaggio and Babe Herman, who played against him on the West Coast, said Satchel was the toughest pitcher they ever faced. Paige estimated that in his career he pitched 2,600 games, 300 shutouts, and 55 no-hitters.

Finally, with Satchel at an undetermined age, Bill Veeck brought him to the major leagues in 1948, and the rest is history. As the oldest rookie ever to play major league baseball, he registered a 6-1 record and a 2.48 ERA down the stretch to help pitch the Indians to the pennant and World Series victory that year.

Reunited with the consummate showman Veeck on the St. Louis Browns in 1951, Satchel relaxed in his own personal rocking chair in the bullpen when not in action and kept the legend going. Twelve years after making appearances in the major league All Star games of 1952-1953, Satch, at the dubious age of fifty-nine, pitched 3 innings for the Kansas City A’s in 1965 to become the oldest man to pitch in a major league game, contributing still another chapter to the ever expanding collection of “Satchel stories.”

In 1971, on the proudest day of his life, Satchel was elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame, becoming the first player elected from the Negro Leagues. In the years after his induction, Satch was continuing to follow his own rare advice, “Don’t look back, something might be gaining on you,” when, indeed, something finally did catch up with him. On June 8, 1982, death stilled the baseball immortal.

Source: James A. Riley, The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues, New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, Inc., 1994.