Abolition, Black History

Maria W. Stewart (Maria Miller) (1803 – February 6, 1880) was an African-American journalist, lecturer, abolitionist, and women’s rights activist. Although her career was brief it was very striking. Maria W. Stewart started off her career as a domestic servant. She later became an activist.

Maria W. Stewart (Maria Miller) (1803 – February 6, 1880) was an African-American journalist, lecturer, abolitionist, and women’s rights activist. Although her career was brief it was very striking. Maria W. Stewart started off her career as a domestic servant. She later became an activist.

She was the first American woman to speak to a mixed audience of men and women, whites and black. She was also the first African- American woman to lecture about women’s rights, make a public anti-slavery speech and the first African-American woman to make public lectures. Stewart has had two pamphlets published in the Liberator, including “Religion and Pure Principles of Morality, the Sure Foundation on Which We Must Build”. In this pamphlet she advocated abolition and black autonomy. Her second pamphlet was more religious-based. (more…)

Abolition, Black History

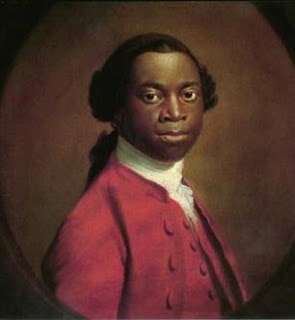

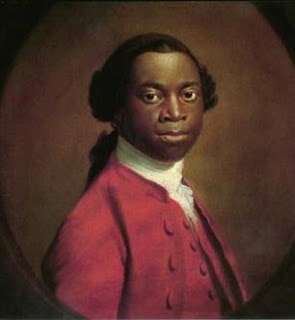

Olaudah Equiano

aka Gustavus Vassa

Captured far from the African coast when he was a boy of 11, Olaudah Equiano was sold into slavery, later acquired his freedom, and, in 1789, wrote his widely-read autobiography, The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, the African.

The youngest son of a village leader, Equiano was born among the Ibo people in the kingdom of Benin, along the Niger River. He was “the greatest favourite with [his] mother.” His family expected to follow in his father’s footsteps and become a chief, an elder, a judge. Slavery was an intregal part of the Ibo culture, as it was with many other African peoples. His family owned slaves, but there was also a continual threat of being abducted, of becoming someone else’s slave. This is what happened, one day, while Equiano and his sister were at home alone. (more…)

Abolition, Black History

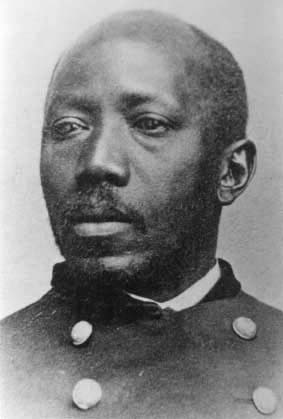

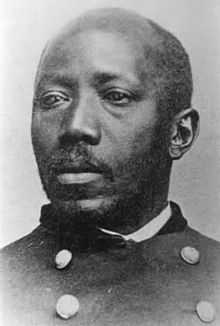

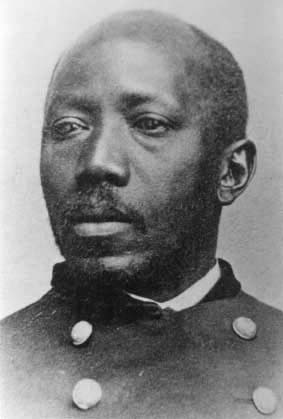

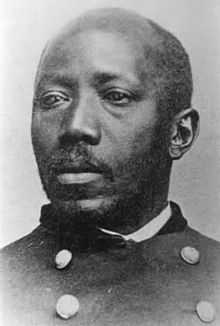

Martin R. Delaney

Martin Robison Delany (May 6, 1812 – January 24, 1885) was an African-American abolitionist, journalist, physician, soldier and writer, and arguably the first proponent of black nationalism.Delany is credited with the Pan-African slogan of “Africa for Africans.”

Born as a free person of color in Charles Town, Virginia (now in West Virginia) and raised in Chambersburg and Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, Delaney trained as physician’s assistant. During the cholera epidemics of 1833 and 1854 in Pittsburgh, Delany treated patients although many doctors and residents fled the city out of fear of contamination. In this period, people did not know how the disease was transmitted.

In 1850, Delany was one of the first three black men admitted to Harvard Medical School, but all were dismissed after a few weeks because of widespread protests by white students. (more…)

Abolition, Black History

Mary Livermore

Mary Ashton Rice was born in Boston, Massachusetts on December 19, 1820 to Timothy Rice and Zebiah Vose (Ashton) Rice. She was a direct descendant of Edmund Rice an early Puritan immigrant to Massachusetts Bay Colony. She attended school at an all-female seminary in Charlestown, Massachusetts, and read the entire bible every year until the age of 23. She graduated from the seminary in 1836, but stayed there as a teacher for two years. In 1839, she started a job as a tutor on a Virginia plantation, and after witnessing the cruel institution of slavery, she became an abolitionist. In 1842, she left the plantation to take charge of a private school in Duxbury, Massachusetts, where she worked for three years.

She married Daniel P. Livermore, a Universalist minister in May 1845, and in 1857, Livermore and her husband moved to Chicago. She published a collection of nineteen essays entitled Pen Pictures in 1863. As a member of the Republican party, Livermore campaigned for Abraham Lincoln in the 1860 presidential election. (more…)

Abolition, Black History

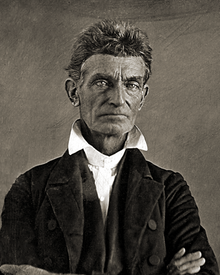

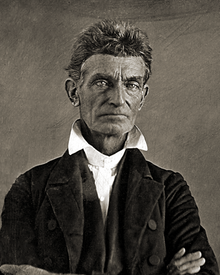

John Brown

John Brown was a man of action — a man who would not be deterred from his mission of abolishing slavery. On October 16, 1859, he led 21 men on a raid of the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia. His plan to arm slaves with the weapons he and his men seized from the arsenal was thwarted, however, by local farmers, militiamen, and Marines led by Robert E. Lee. Within 36 hours of the attack, most of Brown’s men had been killed or captured.

John Brown was born into a deeply religious family in Torrington, Connecticut, in 1800. Led by a father who was vehemently opposed to slavery, the family moved to northern Ohio when John was five, to a district that would become known for its antislavery views. (more…)

Abolition, Black History

- Martin R. Delany

b. May 6, 1812, Charles Town, Va., U.S.–d. Jan. 24, 1885, Xenia, Ohio), U.S. black Abolitionist, physician, and editor in the pre-Civil War period; his espousal of black nationalism and racial pride anticipated expressions of such views a century later.

In search of quality education for their children, the Delanys moved to Pennsylvania when Martin was a child. At 19, while studying nights at a Negro church, he worked days in Pittsburgh. Embarking on a course of militant opposition to slavery, he became involved in several racial improvement groups. Under the tutelage of two sympathetic physicians he achieved competence as a doctor’s assistant as well as in dental care, working in this capacity in the South and Southwest (1839). (more…)

Maria W. Stewart (Maria Miller) (1803 – February 6, 1880) was an African-American journalist, lecturer, abolitionist, and women’s rights activist. Although her career was brief it was very striking. Maria W. Stewart started off her career as a domestic servant. She later became an activist.

Maria W. Stewart (Maria Miller) (1803 – February 6, 1880) was an African-American journalist, lecturer, abolitionist, and women’s rights activist. Although her career was brief it was very striking. Maria W. Stewart started off her career as a domestic servant. She later became an activist.