Black History, Business, Other

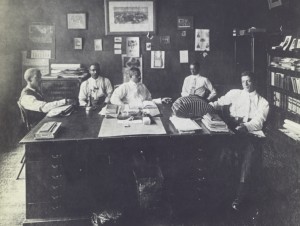

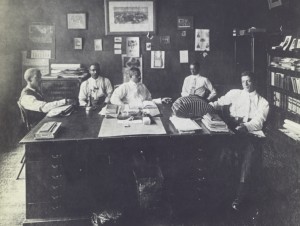

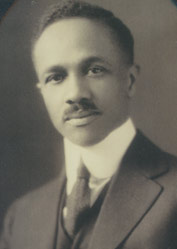

Officers of the North Carolina Mutual Life Insurance Company in 1911

Since its beginning in 1898, North Carolina Mutual Life Insurance Company has grown to become one of the nation’s most widely-known and successful business institutions. It is the only insurance company domiciled in North Carolina with a charter dated before 1900. North Carolina Mutual is the oldest and largest African American life insurance company in the United States.

The Company’s seven organizers were men who were active in business, educational, medical and civic life of the Durham community. An early financial crisis tested their resolve and the company was reorganized in 1900 with only John Merrick and Dr. Aaron M. Moore remaining. Charles C. Spaulding was named General Manager, under whose direction the company grew and achieved national prominence. (more…)

Black History, Business

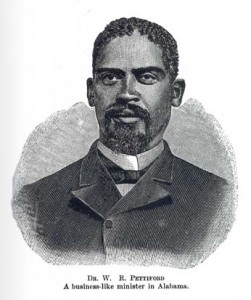

The Penny Savings Bank, founded by Reverend William Reuben Pettiford in Birmingham in 1890, was the first black-owned and black-operated financial institution in Alabama. Created as a necessity of de facto and later codified segregation, the bank backed and encouraged development of black businesses, especially in urban areas, as well as savings by African Americans, until its closing in 1915.

The Penny Savings Bank, founded by Reverend William Reuben Pettiford in Birmingham in 1890, was the first black-owned and black-operated financial institution in Alabama. Created as a necessity of de facto and later codified segregation, the bank backed and encouraged development of black businesses, especially in urban areas, as well as savings by African Americans, until its closing in 1915.

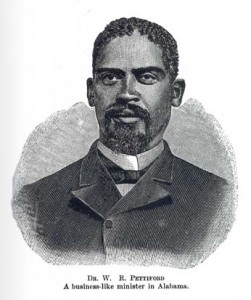

William Reuben Pettiford

William Reuben Pettiford was born to free parents in North Carolina in 1847. He moved to Alabama in 1869 to seek better educational and financial opportunities. After seven years of studying while holding down jobs, Pettiford completed his degree at the Lincoln Normal School (a predecessor of Alabama State University) in Marion, Perry County. In 1877, Pettiford became a teacher at Selma University and simultaneously entered the theological department of the school, taking courses from President Harrison Woodsmall.

Three years later, he voluntarily severed his connection with the school to become pastor of the First Baptist Church of Union Springs, where he also served as principal of the city school for African Americans. In 1883, he accepted the pastorate of the First Colored Baptist Church of Birmingham, later named the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church, at the urging of state Baptist leaders and educator Booker T. Washington, who assured him that he could provide necessary leadership for Birmingham’s expanding black population.

(more…)

Black History, Business, Firsts

Madame C.J. Walker

Born Sarah Breedlove on December 23, 1867 on a Delta, Louisiana plantation, this daughter of former slaves transformed herself from an uneducated farm laborer and laundress into one of the twentieth century’s most successful, self-made women entrepreneurs.

Orphaned at age seven, she often said, “I got my start by giving myself a start.” She and her older sister, Louvenia, survived by working in the cotton fields of Delta and nearby Vicksburg, Mississippi. At 14, she married Moses McWilliams to escape abuse from her cruel brother-in-law, Jesse Powell.

Her only daughter, Lelia (later known as A’Lelia Walker) was born on June 6, 1885. When her husband died two years later, she moved to St. Louis to join her four brothers who had established themselves as barbers. (more…)

Black History, Business

Mary Smith Peake

The year was 1861. The American Civil War had shortly begun and the Union Army held control of Fort Monroe in Hampton, Virginia at the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay. In May of that year, Union Major General Benjamin Butler decreed that any escaping slaves reaching Union lines would be considered “contraband of war” and would not be returned to bondage. This resulted in waves of enslaved people rushing to the fort in search of freedom. A camp to house the newly freed slaves was built several miles outside the protective walls of Fort Monroe. It was named “The Grand Contraband Camp” and functioned as the United States’ first self-contained African American community.

In order to provide the masses of refugees some kind of education, Mary Peake, a free Negro, was asked to teach, even though an 1831 Virginia law forbid the education of slaves, free blacks and mulattos. She held her first class, which consisted of about twenty students, on September 17, 1861 under a simple oak tree. This tree would later be known as the Emancipation Oak and would become the site of the first Southern reading of the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863. Today, the Emancipation Oak still stands on the Hampton University campus as a lasting symbol of the promise of education for all, even in the face of adversity.

Black History, Business, Firsts, Other

John W Cromwell

In 1921, John W. Cromwell, Jr., became the first African-American to earn the designation of CPA, some 25 years after the first CPA certificate was granted in the United States. Cromwell was a member of one of the leading African-American families in the country. His father was a teacher, political activist, attorney, and chief examiner for the U.S. Post Office. Cromwell’s older sister, Otelia, was the first African-American alumna of Smith College and went on to earn a Ph.D. in English at Yale. Cromwell was exceptional himself. He graduated from Dartmouth as the best student in science in the class of 1906. A year later he completed his master’s degree there.

The profession most open to African-Americans at the time was teaching. After finishing at Dartmouth, Cromwell returned home to Washington, D.C., and became a mathematics teacher at the Dunbar School, the most prestigious black high school in the country.

Fifteen years passed before John Cromwell became a CPA. He was not allowed to sit for the CPA exam in Washington, D.C., Virginia, or Maryland. In addition, all those places had experience requirements. The biggest barrier to African-Americans in becoming CPAs has always been the experience requirement: In order to become a CPA you have to work for a CPA, and for the first two-thirds of the last century, most firms would not hire African-Americans. (more…)

Black History, Business

Macon Bolling Allen

Macon Bolling Allen is believed to be the first black man in the United States who was licensed to practice law. Born Allen Macon Bolling in 1816 in Indiana, he grew up a free man. Bolling learned to read and write on his on his own and eventually landed his first a job as a schoolteacher where he further refined his skills.

In the early 1840s Bolling moved from Indiana to Portland, Maine. There he changed his name to Macon Bolling Allen and became friends with local anti-slavery leader General Samuel Fessenden, who had recently began a law practice. Fessenden took on Allen as an apprentice/law clerk. By 1844 Allen had acquired enough proficiency that Fessenden introduced him to the Portland District court and stated that he thought Allen should be able to practice as a lawyer. He was refused on the grounds that he was not a citizen, though according to Maine law anyone “of good moral character� could be admitted to the bar. He then decided to apply for admission by examination. After passing the exam and earning his recommendation he was declared a citizen of Maine and given his license to practice law on July 3, 1844.

(more…)