Black History, Dance, Entertainment

Bill Bojangles Robinson

Bill “Bojangles” Robinson (May 25, 1878 – November 25, 1949) was an American tap dancer and actor of stage and film. Audiences enjoyed his understated style, which eschewed the frenetic manner of the jitterbug in favor of cool and reserve; rarely did he use his upper body, relying instead on busy, inventive feet, and an expressive face.

A figure in both the black and white entertainment worlds of his era, he is best known today for his dancing with Shirley Temple in a series of films during the 1930s, and for starring in the 1943 musical Stormy Weather, loosely based on Robinson’s own life.

Black History, Entertainment

Caterina Jarboro

Caterina Jarboro (1903-1986) was a pioneering African American opera singer. In 1933 — twenty-two full years before Marian Anderson’s début at the Metropolitan Opera — impresario Alfredo Salmaggi hired Jarboro to sing with his opera company at the Hippodrome.

She was thus the first black opera singer ever to sing on an opera stage in America. (This milestone earned Salmaggi special recognition from First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt. (more…)

Black History, Entertainment

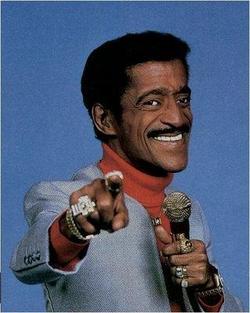

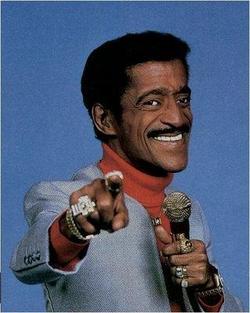

Sammie Davis Jr.

1925 to 1990. In the over hyped world of popular music music, there are legends, and then there are Legends with a capital L. There’s no doubting which category Sammy Davis Jr falls into. For a staggering 60 years, from his debut as a four year old child star in the late 1920’s to his untimely death in 1990 at the age of 64, he more than justified his title of ‘Mr Entertainment’ and when he wasn’t inspiring headlines on stage he was making news of it, as a founder member of the Rat Pack with fellow superstars Frank Sinatra and Dean Martin.

He owed his early start to his parents, vaudeville star Sammy Davis Sr and Puerto Rican ‘Baby Sanchez, who performed with the youngsters adopted uncle, Will Mastin, in his act ‘Holiday In Dixieland’. But Sammy Jr soon became the star of the show as the newly rechristened ‘Will Mastin’s Gang, Featuring Little Sammy’ acknowledged. When the authorities forbade him to appear, so legend has it his father shrugged his shoulders, gave his son a rubber cigar and billed him as a ‘dancing midget’. (more…)

Black History, Entertainment

Sonny Boy Williamson

Born John Lee Williamson in Jackson, Tennessee. One of the founding members of the post-War Chicago blues scene, Sonny Boy Williamson did more to popularize the harmonica than any of his contemporaries. His musical and geographical migration from the deep South up the Mississippi to Chicago exemplifies his rise in popularity. Williamson never realized his full potential as a musician, as he was tragically murdered at the peak of his career.

He taught himself to play harmonica as a teenager and by his late teens was touring the Depression-era South, playing with the likes of Big Joe Williams and Robert Nighthawk. With his masterful harp (harmonica) playing and country-blues sound, Williamson fused a new band format with the harmonica as lead instrument. (more…)

Black History, Entertainment

WGPR-TV Detroit

WGPR-TV (Where God’s Presence Radiates) was the first television station in the United States owned and operated by African Americans. The station, located in Detroit, Michigan, was founded by William Venoid Banks. WGPR-TV marketed toward the urban audience in Detroit, Michigan, which in that market meant programming for the African American community.

WGPR-TV first aired on September 29, 1975 on channel 62 in Detroit, Michigan. Station founder William Venoid Banks was a Detroit attorney, minister and prominent member of the International Free and Accepted Modern Masons, an organization he founded in 1950. The Masons owned the majority of stock in WGPR-TV. The station initially broadcast religious shows, R&B music shows, off-network dramas, syndicated shows and older cartoons. (more…)

Black History, Entertainment

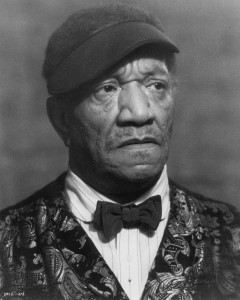

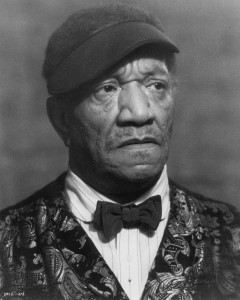

Redd Foxx

1922-1991. Born John Elroy Sanford in St. Louis, Missouri, Foxx made his mark in the TV smash Sanford and Son (1972?77) after many years of odd jobs and short stretches on the night club circuit, including a kitchen job with Malcolm Little who would later be known as Malcolm X.

Foxx hit it big in Las Vegas in 1968, but didn’t make the celluloid jump until the 1970 film Cotton Comes to Harlem. The role brought him to the attention of producers Bud Yorkin and Norman Lear who decided to cast Foxx in Sanford and Son, his first major success. The show was followed by others, including The Redd Foxx Comedy Hour (1977-78) and the Redd Foxx Show (1986).

He later co-edited The Redd Foxx Encyclopedia of Black Humor (1977).