Black History, Civil Rights, Government, Politics

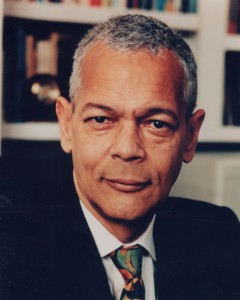

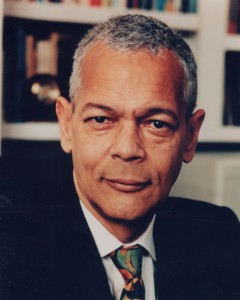

Julian Bond

HORACE JULIAN BOND (Jan. 14, 1940 – Aug. 15, 2015), U.S. legislator and black civil-rights leader, best known for his fight to take his duly elected seat in the Georgia House of Representatives. The son of prominent educators, Bond attended Morehouse College in Atlanta (B.A., 1971), where he helped found a civil-rights group and led a sit-in movement intended to desegregate Atlanta lunch counters.

In 1960 Bond joined in creating the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), and he later served as communications director for the group. In 1965 he won a seat in the Georgia state legislature, but his endorsement of a SNCC statement accusing the United States of violating international law in Vietnam prompted the legislature to refuse to admit him. (more…)

Black History, Politics, Slavery

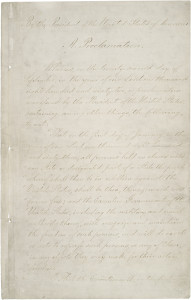

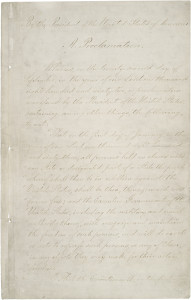

Emancipation Proclamation

President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, as the nation approached its third year of bloody civil war. The proclamation declared “that all persons held as slaves” within the rebellious states “are, and henceforward shall be free.”

Despite this expansive wording, the Emancipation Proclamation was limited in many ways. It applied only to states that had seceded from the Union, leaving slavery untouched in the loyal border states. It also expressly exempted parts of the Confederacy that had already come under Northern control. Most important, the freedom it promised depended upon Union military victory.

Although the Emancipation Proclamation did not end slavery in the nation, it captured the hearts and imagination of millions of Americans and fundamentally transformed the character of the war. After January 1, 1863, every advance of federal troops expanded the domain of freedom. Moreover, the Proclamation announced the acceptance of black men into the Union Army and Navy, enabling the liberated to become liberators. By the end of the war, almost 200,000 black soldiers and sailors had fought for the Union and freedom. (more…)

Black History, Politics

Carol Moseley Braun

CAROL MOSELEY (b. Aug. 16, 1947, Chicago, Ill., U.S.), U.S. senator from Illinois who, in 1992, became the first African-American woman elected to the U.S. Senate. Moseley-Braun attended the University of Illinois at Chicago and received a law degree from the University of Chicago.

She worked as an assistant U.S. attorney before her election to the Illinois House of Representatives in 1978. During her 10 years there she became known for her advocacy of health-care and education reform and gun control. She was named assistant leader for the Democratic majority.

In 1988-92 Moseley-Braun served as Cook county recorder of deeds. Displeased with U.S. Senator Alan Dixon’s support of U.S. Supreme Court nominee Clarence Thomas, she ran against Dixon in the 1992 Democratic primary. Though poorly financed, she won an upset victory over Dixon on her way to capturing a seat in the Senate. (more…)

Black History, Politics

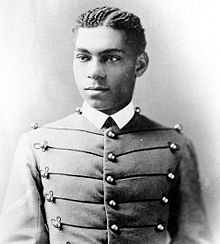

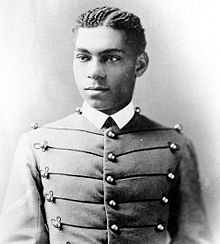

- Henry O. Flipper

1856-1940 – Henry Flipper was the first black to graduate from the U.S. Military Academy at West Point (1877) and was the first black to be assigned to a command position in a black unit following the Civil War. However, Flipper became the victim of a controversial court-martial proceeding�he was charged with “conduct unbecoming to an officer and a gentleman” and received a dishonorable discharge.

Despite repeated attempts to vindicate himself, at the time of his death he still had not cleared his record. Years later, however, the sentence was reversed. He was awarded an honorable discharge posthumously, and his remains were reburied with full honors at Arlington Cemetery. (more…)

Black History, Politics

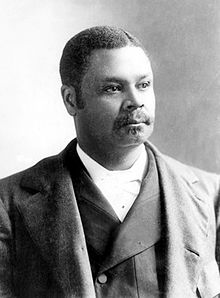

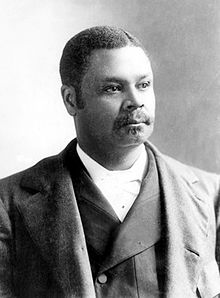

George H. White

George Henry White (18 Dec. 1852-28 Dec. 1918), lawyer, legislator, congressman, and racial spokesman, was born near Rosindale in Bladen County, the son of Wiley F. and Mary White. It is possible that he was born into slavery, although the evidence on this is contradictory. He did attend public schools in North Carolina and received training under D. P. Allen, president of the Whitten Normal School in Lumberton.

In 1876 he was an assistant in charge of the exhibition mounted by the U.S. Coast Survey at the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia. After graduation from Howard University in 1877, he was principal of the Colored Grade School, the Presbyterian parochial school, and the State Normal School in New Bern. He studied law under Judge William J. Clarke and received a license to practice in North Carolina in 1879. (more…)

Black History, Other, Politics

Arthur Spingarn

Arthur Barnette Spingarn (1878-1971) was an American leader in fight for civil rights for African Americans.

Spingarn was born into a well-to-do family. He graduated from Columbia College in 1897 and from law school in 1899. He was one of a small group of white Americans who decided in the 1900s (decade)to support the radical demands for racial justice being voiced by W. E. B. Du Bois in contrast to the more ameliorative views of Booker T. Washington. He served as head of the legal committee of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and one of its vice-presidents starting in 1911. (more…)