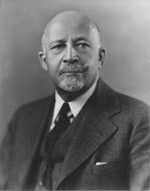

(b. February 23, 1868, Great Barrington, Mass.; d. August 27, 1963, Accra, Ghana), writer, social scientist, critic, and public intellectual; cofounder of the Niagara Movement, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), and the Pan-African Congress; editor of the NAACP magazine, The Crisis.

Along with Frederick Douglass and Booker T. Washington, historians consider W. E. B. Du Bois one of the most influential African Americans before the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s. Born only six years after emanicipation, Du Bois was active well into his nineties, dying in 1963, on the eve of the March on Washington.

Despite near-constant criticism for his often contradictory social and political opinions, he was accused, at various times, of elitism, communism, and black separatism, Du Bois remained throughout his long life black America’s leading public intellectual. Born in a small western Massachusetts town, Du Bois and his mother,- his father had left the family when he was young – were among the few African American residents.

Of his heritage, Du Bois wrote that it included “a flood of Negro blood, a strain of French, a bit of Dutch, but, Thank God! No ‘Anglo-Saxon’….” After an integrated grammar-school education, Du Bois attended the historically black Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee, and then Harvard University, from which he received a bachelor’s degree in 1890. That fall Du Bois began graduate work in history at Harvard under legendary professors George Santayana, William James, and Josiah Royce; Du Bois was especially influenced by Albert Bushnell Hart, one of the fathers of the new science of sociology. After two years at the University of Berlin (1892-1894), he received a Ph.D. from Harvard in 1895. His dissertation, “The Suppression of the African Slave-Trade to the United States of America, 1638-1870” was published in 1896 as the first volume in the Harvard Historical Studies series.

Despite exceptional credentials, discrimination left Du Bois with no options other than a job at Wilberforce College, a small black school in Ohio. Arriving in 1895, Du Bois left a year later with his wife, former student Nina Gomer. They went to Philadelphia, where the University of Pennsylvania had invited Du Bois to conduct a sociological study of that city’s black neighborhoods. The work led to The Philadelphia Negro (1899), which provided the model for a series of monographs he wrote while at Atlanta University, whose faculty he joined in 1897. As a young sociologist, he sought to “study [social problems] in the light of the best scientific research.” But the persistence of segregation, discrimination, and lynching led Du Bois to increasingly feel that “one could not be a calm, cool, and detached scientist while Negroes were lynched, murdered, and starved….”

In 1903 Du Bois published his first collection of essays, The Souls of Black Folk, which many have called the most important book ever written by an African American. In it he identified “the color line” as the twentieth century’s central problem, and dismissed the accommodationism advocated by Booker T. Washington. “[When] Mr. Washington apologizes for injustice,” Du Bois wrote, “does not rightly value the privilege and duty of voting, belittles the emasculating effects of caste distinctions, and opposes the higher training and ambition of our brighter minds…we must unceasingly and firmly oppose [him].” In 1905, Du Bois joined with William Monroe Trotter, militant editor of the black newspaper the Boston Guardian, in forming the Niagara Movement, a short-lived effort to secure full civil and political rights for African Americans. In its wake, Du Bois helped found the most influential civil rights organization of the twentieth century: the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

Unlike the Niagara Movement, the NAACP was an interracial organization from the start. Its leadership was largely white; as director of publications and research, Du Bois was the only African American among its early officers. In 1910 Du Bois left Atlanta for the NAACP’s New York City headquarters where he founded The Crisis, the association’s magazine. As editor he published the work of Langston Hughes, Countee Cullen, and other Harlem Renaissance literary lights as well as his own wide-ranging and provocative opinions. From 1910 until his resignation as editor in 1934, Du Bois’s editorials reveal the continuing evolution of his political thought. Early calls for integration and an end to lynching hewed the NAACP line, while Du Bois’s pleas for African American participation in World War I brought scorn from more radical black voices. His insistence on absolute equality for “the talented tenth” of black intellectual elites coexisted uneasily with arguments for self-segregation and technical training for the black masses. Such shifting opinions, along with his sometimes haughty self-assurance, meant that, as one biographer has noted, Du Bois would always have “influence, not power.”

Increasingly, Du Bois looked beyond American race relations to international economics and politics. In 1915 he wrote The Negro, a sociological examination of the African diaspora. In 1919 he helped organize the second Pan-African Congress. Visiting Africa in the 1920s, Du Bois wrote that his chief question was whether “Negroes are to lead in the rise of Africa or whether they must always and everywhere follow the guidance of white folk.”

Along with anti-imperialism, Du Bois also expressed interest in socialism, possibly in response to the disproportionate effect the Great Depression was having on African Americans as well his favorable impressions of a visit to the Soviet Union in 1926. Meanwhile, starting with a new essay collection, Darkwater: Voices From Within the Veil (1920), Du Bois’s writing became more militant and controversial, and conflicts with NAACP secretary Walter F. White led to Du Bois’s resignation as editor of The Crisis in 1934.

Returning to Atlanta University, Du Bois continued to write weekly opinion columns in black newspapers, as well as books such as Black Reconstruction in America (1934); Black Folk: Then and Now (1939); and Dusk of Dawn: An Autobiography of a Concept of Race (1940). In 1939 Du Bois founded Phylon, a journal devoted to race and cultural issues, whose radical nature may have contributed to his forced resignation from Atlanta University in 1944. Then in his mid-seventies, Du Bois did not retire but instead rejoined the NAACP staff (although he did not resume editorship of The Crisis). Declaring that he would spend “the remaining years of [his] active life” in the fight against imperialism, Du Bois helped reorganize the Pan-African Congress, which in 1945 elected him its international president. That same year he published Color and Democracy: Colonies and Peace, and in 1947 produced The World and Africa. Du Bois’s outspoken criticism of American foreign policy and his involvement with the 1948 presidential campaign of Progressive Party candidate Henry Wallace led to his dismissal from the NAACP in the fall of 1948.

During the 1950s, Du Bois’s continuing work with the international peace movement and open expressions of sympathy for the Soviet Union drew the censure of the United States government, and further isolated Du Bois from the civil rights mainstream. In 1951, at the height of the cold war, he was indicted under the Foreign Agents Registration Act of 1938. While he was acquitted of that charge, the Department of State refused to issue Du Bois a passport in 1952, barring him from foreign travel until 1958. Once the passport ban was lifted, Du Bois and his wife, the writer Shirley Graham Du Bois, traveled extensively, visiting England, France, Belgium and Holland, as well as China and the Soviet Union, and much of the eastern bloc. On May 1, 1959, he was awarded the Lenin Peace Prize in Moscow. In 1960 Du Bois attended his friend Kwame Nkrumah’s inauguration as the first president of Ghana; the following year the Du Boises accepted Nkrumah’s invitation to move there and work on the Encyclopaedia Africana, a project that was never completed. Du Bois died at the age of 94, six months after becoming a Ghanaian citizen.